The Cloak of Invisibility

at what point does trying to make oneself visible become morphing yourself to fit a mould which was never designed for you?

Over the past couple of months, I have been thinking about the idea of invisibility vs. visibility, the complex interplay between these two polarities one can experience, and how it relates to queer identity.

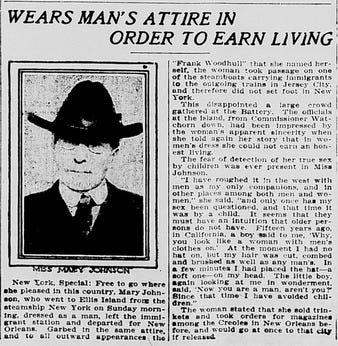

These reflections have been prompted by some discussions with fellow substacker Finn Schubert. In his post Trans Ancestor Frank Woodhull and the Stories That Come From Necessity, Finn recounts a significant moment in the life of Frank Woodhull, who was a transgender man living in the 19th Century, when he became embroiled in a national news story after being detained at Ellis Island, due to his assigned-at-birth sex not matching his gender presentation.

By the time he was due to disembark at Manhattan, crowds of people were waiting to get a look at this mysterious figure. But what he did instead was get on a ferry to New Jersey, evading the crowds, after which it’s thought that he travelled further south to New Orleans. There is no historical record of him after that. I think many of us, put in his position, would have done the same.

What is fascinating about this story, for me, is the idea that for Woodhull, the best option was to disappear completely from the public eye. In an age where our identities are expected to be so heavily performed for the public, and it can feel like your existence is made into a spectacle, I’m fascinated by the idea that Frank chose to do the complete opposite of that and presumably just continue going about his life out of public view. I think it was a very smart move.

Finn mentions in his aforementioned post that many historical trans people chose to live their lives outside of the historical record - in other words, out of view of the culture’s dominant narrative - and it makes me wonder whether the incentive these days to parade our identities around like articles of clothing, rather than seeing them as components of how we understand and experience life, constricts us rather than liberates us.

Much of living in our current world as a queer person revolves around the cultural idea of the “closet.” In order to be recognised by the culture as a queer person, one must “come out,” often in a rather dramatic fashion, and declare themselves as such, in a kind of performance of being “different.” Gender theorist Judith Butler has some interesting insights about how the closet operates as a kind of trap for queer individuals:

"Is the 'subject' who is 'out' free of subjection and finally in the clear? Or could it be that the subjection that subjectivates the gay or lesbian subject in some ways continues to oppress, or oppresses most insidiously, once ‘outness' is claimed? [...] If I claim to be a lesbian, I ‘come out’ only to produce a new and different ‘closet.’ [...] being 'out' always depends to some extent on being 'in'; it gains its meaning only within that polarity. Hence, being ‘out’ must produce the closet again and again in order to maintain itself as ‘out.’”1

What Butler so incisively articulates here is that these notions of “out” and “in” are products of the heterosexual matrix, and claiming a queer identity on the terms of a heteronormative culture does not in fact help the individual but reinforces the very power structure by which the marginalisation of queer people is enacted. Once you are “out,” you are then vulnerable to judgement and/or attack, sometimes even within queer communities.

Visibility does not always help us if what we want is to be able to live peacefully and without threat of violence. However, the cost of invisibility can also be dear - chronic repression of one’s sexuality or gender identity can be detrimental to the psyche of a queer person. So then the question is: who do we want to be seen by - who do we want to be visible to - and who would we rather slip past unnoticed?

The motif of the cloak of invisibility in literature can be observed throughout history - it appears in myths and fairy tales as a means for trickery, or as an aid for fulfilling a hero’s quest. More recently, it has appeared in the Harry Potter series. In these stories the cloak of invisibility is necessary to fulfil some task or to evade capture, and usually to obtain something important or valuable. And so it is at certain times in our lives, when we have to go under the radar to fulfil a personal mission and obtain something important for our self-development.

For many people, there is a pivotal moment in their life where they have to retreat from the world and be invisible for a while, such as after a traumatic event or bereavement, or as a way of coming to terms with their past and beginning to heal. In psychological terms, this is called the cocoon stage of healing, or the chrysalis stage. In these circumstances invisibility is necessary to obtain the hidden treasure, which is our own deeper nature, the seed of authenticity, or what Jung termed the archetype of the Self. Under the cloak of invisibility, we can hide from the din of society and nourish our inner lives.

On a personal note, I have often found quietness and invisibility to be a kind of superpower in a culture which is all about image, ego, and being the loudest person in the room. I’m not saying I never talk, but I find when I encounter people who are domineering or aggressive, it’s better to stay quiet and choose my words carefully rather than letting the person force me to be like them.

Audre Lorde writes that “your silence will not protect you” - but, while sometimes that is true, sometimes it isn’t. Silence can be more powerful than an aggressive defence, sometimes. Of course, it’s a privilege to have the space and time to even consider this approach - so many are just trying to survive - but there comes a point where fighting fire with fire becomes just a huge ball of flames, and distinguishing between one side and the other becomes impossible. Opting for a quieter, more considered approach to conflict might be more effective in actually getting what we want.

There is something to be said for publicly owning one’s identity to further equal rights causes, but at what point does trying to make oneself visible become morphing yourself to fit a mould which was never designed for you?

I find this an impossible thing to reconcile. On one hand, I feel a desire to completely eschew these dominant narratives and live in my own world where none of it exists; on the other hand, the limitations which culture imposes are real and impact us regardless of how we orient ourselves to them. I suppose it’s ultimately about finding a balance between doing what you need to do to get by in the society you live in, and also creating a space in which to live on your own terms, unfettered by anyone’s idea of who you are or should be.

Schubert has written at length about writing new narratives for himself. This is partly due to his somewhat unique position as a currently pregnant man who presents in a masculine fashion - there is no mould, no archetypal precedent, for this type of person. But I also think the idea of writing your own narrative can be applied to the way we live in general.

If the proposed model for how someone like you is supposed to live doesn’t work for you, why not write a new one? And if there is no pre-existing narrative for someone who has your body and your identity, that can be liberating in a way, because you get to write your own narrative, your own story. People are infinitely variable and multitudinous; there is room for all of our stories and experiences in our common experience of being human.

I’ll leave you with this message: It’s okay to be invisible for a while, or a long time, if that’s what you want to do. Invisibility can protect you, it can be a safe place. But know when it is time to draw off the cloak, to reemerge, and offer your gifts to the world - for the world can only be better with them in it.

Thanks for reading! If you’d like to see more, consider subscribing to get future posts right to your inbox. And sharing really helps to get the word out.

Until next time.

from “Imitation and Gender Insubordination,” in The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, pp. 308-9.