Freedom, Longing, and the Closet in Kate Bush's "Kashka from Baghdad"

"they know the way to be happy"

If you hadn’t heard of Kate Bush before, you probably know of her now, after her 1985 single “Running Up That Hill” shot up the charts across the globe last year. The song was featured in a pivotal scene of the Netflix show Stranger Things, where the song acts as a talisman for the character Max as she faces her demons - by which I mean an actual demon. “Running Up That Hill” is Max’s favourite song, and her friends use it as a lifeline to pull her back from the brink of death in an alternate realm.

As a Kate Bush fan of many years, it’s greatly heartening to see a generation of younger people now discovering her music because of this. Bush’s back catalog is incredibly rich and varied, and to discover such a treasure trove of music is a very special experience to have.

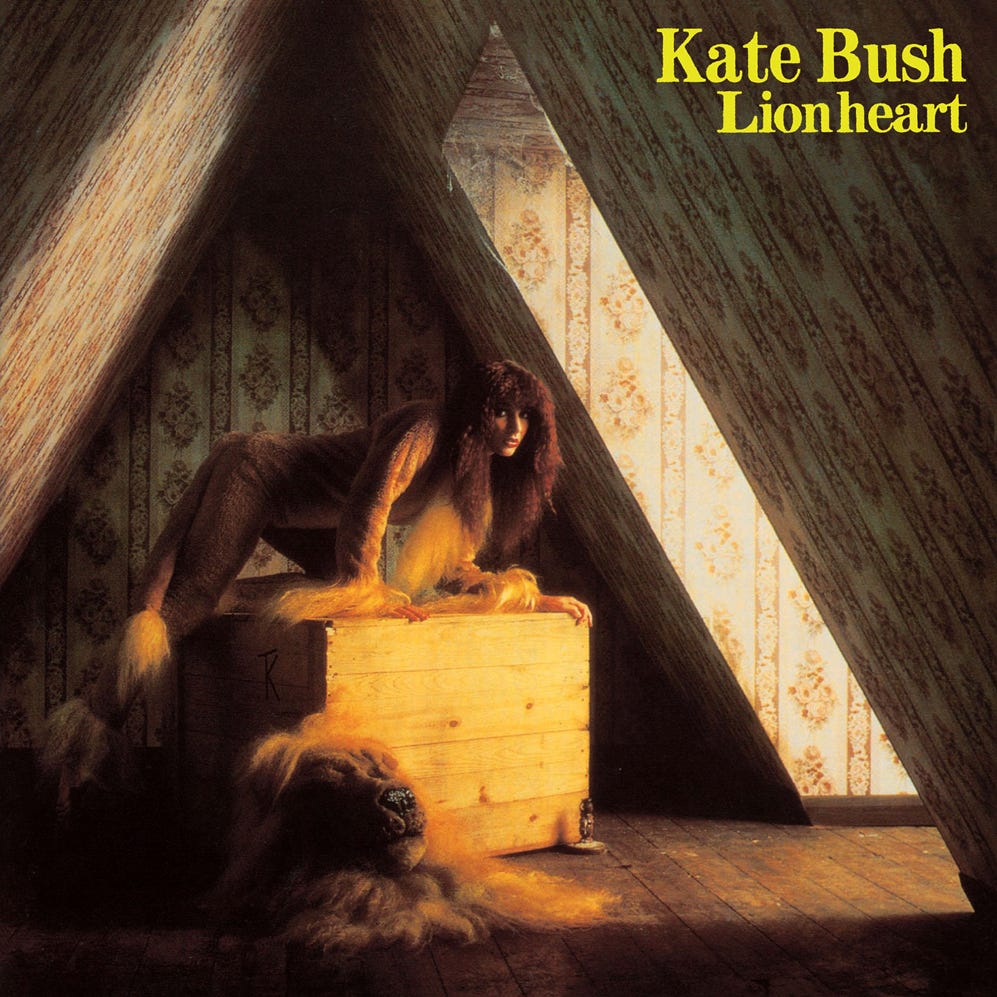

Today I want to look at another of her songs, called “Kashka from Baghdad”. This is a song from early in her career which appears on Lionheart, her second album, released in 1978. The song strikes me as unique in Bush’s discography, and also as a song in general, because the song is about a gay relationship between two men.

This wasn’t a topic many songwriters were willing to explore at this time. Queer music wasn’t exactly non-existent then - for example, Sylvester released the queer disco anthem “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)” the very same year - but for a heterosexual woman to be writing about this subject, at this time, feels like an extraordinary thing indeed.

Let’s look at the cultural background for gay rights in Britain in 1978. England and Wales had decriminalised homosexuality only 11 years earlier, in 1967. Scotland wouldn’t follow suit until 1980; Northern Ireland not until 1982.1 The Republic of Ireland wouldn’t decriminalise homosexuality until 1993.2 And let us not forget that decriminalisation doesn’t necessarily mean acceptance - it just meant you couldn’t be thrown in jail for it. The rights and relative freedoms queer folks now enjoy were a long way off. Among other things, the AIDS crisis during the 1980s and 90s continued to stigmatise the queer community in Britain.

Bush was no stranger to writing about taboo subjects: her debut album The Kick Inside included a song about a woman who becomes pregnant by her brother and then kills herself. It’s hard to imagine that this kind of thing would fly nowadays, but it is nonetheless a gorgeous song. She would go on to write other songs exploring similarly complex and difficult subject matter, such as “The Infant Kiss” and “Mother Stands for Comfort”.

Bush is essentially a novelist in song, a storyteller; she chooses to write about fictional scenarios rather than sing about her own experiences, with few exceptions. She often draws on books for her songwriting, such as James Joyce’s novel Ulysses, which inspired “The Sensual World”, and Stephen King’s The Shining, which inspired “Get Out of My House”. Not to mention Wuthering Heights.

But back to the song at hand - the fact that Bush chooses a gay relationship as the subject for a song says something very symbolic: that homosexual relationships are just as worthy of attention as any other; that they are even worthy of writing fiction about. I would imagine that her contemporaries wouldn’t have gone near something like this for fear of it being too ‘controversial’. Not one to be deterred in this way, Bush is notable for her seemingly boundless ability to empathise with a range of different characters, and this song is no exception.

Before I delve in properly, I want to note the fact that the treatment of race in this song is a topic of some contention, in that we know Kashka is from Baghdad but nothing else about his cultural heritage or his experience as a racialised person. I’m not qualified to go into detail about it, and it’s not my focus here, but it’s worth mentioning. What does it mean to introduce a character - in the very first line of the song, as we will see - as being from a foreign land, in a sense to define them in that way, but not to develop the implications of that any further?

The first verse of the song goes: “Kashka from Baghdad / Lives in sin, they say / With another man / But no-one knows who”. Immediately the stigmatisation of homosexuality is made apparent. Though it is not made entirely explicit, the mention of living in “sin”, and with another man, makes it quite obvious what the situation is between them. The song isn’t told from the perspective of Kashka or his partner but by a separate narrator who appears to be observing them, and who doesn’t seem to share this scorn towards them: it’s not the narrator who says they live in sin, it’s “they” - the others.

The scene is further set: “Old friends never call there / Some wonder if life’s / Inside at all / If there’s life inside at all”. This suggests a certain amount of isolation and a lack of freedom. The two men don’t want to make themselves known - no-one comes over, people don’t even seem to know who Kashka’s partner is, and they “never go for walks” either. Understandably, since they are clearly not approved of, and might fear for their safety. They also appear to be the subject of gossip: “But we know the lady who rents the room / She catches them calling à la lune”. This demonstrates clearly the fixation on gay people in a society which rejects them - they are both fascinating and repulsive.

This might be seen to be painting a pretty dismal picture, of a typically repressed gay couple living a typically miserable life, and you might wonder what exactly the point of that is. But then comes the chorus: “At night / They’re seen / Laughing / Loving / They know / The way / To be / Happy”. By day, the two men keep their heads down, but when night comes they emerge, and appear to be having a great time together. And what’s more, they seem to have something the narrator doesn’t, or at least which is different and special in some way, which is a true happiness and love.

It goes on: “I watch their shadows / Tall and slim / In the window opposite / I long to be with them”. This section of the song reveals that the narrator is a neighbour of the couple who watches them regularly, somewhat voyeuristically, sees the way they are together, and is starting to want something of that for themselves. They express a longing to cross the divide that has been put in place by a homophobic culture, and enter the seemingly magical love Kashka and his partner share.

I see this not as a desire for a threesome but as a longing for the true companionship which is identified between the two men. The narrator “hear[s] music from Kashka’s house” and wants to join in their joy, but cannot, as they are part of the majority group who has collectively rejected them. To transgress the cultural boundary and join Kashka would mark them out as well by association. This is the tension the narrator feels - Kashka and his partner represent a projected ideal of love which they long for but cannot have.

Freedom is relative. People will find ways to carve out a sliver of freedom and defiance even under the most oppressive of circumstances. Kashka and his partner don’t have the freedom of being able to integrate into their community, but they have a different kind of freedom that no-one else around them seems to have, which is the ability to love authentically. The narrator of the song has the outer freedom of being able to move freely in their community, but lacks the inner freedom as displayed by the two men, and is feeling increasingly stuck in a staid and repressive society. As the song fades out, these lines repeat: “Won’t you let me laugh? / Let me in your love”.

I’ve written here a few times now about the freedoms that invisibility can offer. When you are out of view of the people who can impose their standards upon you, you can start to find your own identity and access a deeper sense of self. People who are absorbed in the collective have the benefit of belonging to a group of people, but pay the price in having less opportunity to develop their individuality. Those who step outside the circumscribed airs and graces of society sacrifice belonging, but gain a deeper, interior freedom in living true to their own wants and interests.

Kashka and his partner are essentially living in a literal manifestation of the closet - they don’t leave their house, and no-one enters it. They can’t be openly themselves during the day; only at night can they go about their clandestine affairs under cover of darkness. When a culture forces the closet onto queer people, it also imposes an inverted, mirrored closet onto itself, whereby they themselves are cut off from their own feelings which go against the grain of social norms, the feelings which are imaged by the queer person who embodies this transgression. This is essentially what homophobia is: the rejection of the personal shadow.

I don’t mean to suggest that every homophobic person is secretly queer, but what the queer person symbolises - which is difference, curiosity, play - resonates with some correlated part of their unconscious which doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with sexuality, but which is frightening and shameful to them, and causes them to reject the outer image of the queer individual as a mirror of the rejection of their own inner feelings. Those who repress are repressed themselves.

What might happen in the fictional world of “Kashka from Baghdad” after the final notes of the song? Who knows. Might the narrator pluck up the courage to knock on Kashka’s door and introduce themselves? Might they act as a bridge between the outcasts and the community? Or might they be too frightened of the potential negative consequences and things go on basically as they are? In any case, the narrator is sitting in that middle ground: they have recognised a desire to break free of their social conventions in search of deeper human relationships, but haven't been able to actually take that step away from the repressive society they live in. The song takes place on this hinge of unfulfilled longing.

All in all, “Kashka from Baghdad” is a poignant depiction of a gay relationship written at a time when these kinds of stories weren’t really being told except by queer folks themselves, and mostly by novelists rather than songwriters. This is still true to an extent - how many straight people since 1978 have written something like “Kashka from Baghdad”, or, indeed, like any of Bush’s songs? People tend to write about what they know, this is true, and I suppose that serves as further testament to Kate Bush’s remarkable imaginative powers. She seems to be able to put herself in the shoes of any kind of character and the effect is both believable and convincing. “Kashka from Baghdad” is a song about gay love, but it is also just a song about love - and the longing for love is something pretty much all of us can agree on.