In a video from the YouTube channel VICE, we get a peek into what it’s like to attend a gay conversion camp in the US state of Texas. The camp is called Journey Into Manhood, and it aims to help initiate young men into their natural (read: heterosexual) male adulthood. Over the course of a weekend, what takes place mostly consists of group work and storytelling, including putting on a play of Jack and the Beanstalk – ever the symbolic tale – and an exercise in catharsis in which participants vent their frustrations. It’s a kind of psychological theatre, in which people can act out their inner dramas and process traumas, all with the hope that it will bring well-being and renewal.

You’d be forgiven for thinking that this is just another one of those men’s work retreats of the mythopoetic men’s movement – indeed, it uses a lot of the same tropes and is distinctly Jungian in its approach – but make no mistake: the aim of all of this is to eliminate homosexual feelings in these men. That is the ultimate goal from which inner peace and wellbeing is believed to flow. In order to become a man, you have to accept your natural role as masculine provider, as husband, as father, all of which are incompatible with homosexuality, apparently.

In case you’re not entirely sure what conversion therapy is, here’s a summary. Conversion therapies (or conversion practises) seek to change the sexual orientation or gender identity of a person by employing methods designed to motivate them towards a more normative identity. These practises are widely discredited by health organisations, though they are often practised by licensed psychologists, among others.

Though countries are now banning conversion practises, conversion therapy is still legal in the UK – the gender-critical capital of the world – despite claims that we are “a global leader on LGBT rights”. A ban has been on the table for a number of years, but has seen delay after delay after delay. In recent times, there has also been a proliferation of conversion therapies designed specifically to target gender identity. Following the ban of puberty blockers on the NHS earlier this year, these alternative treatments are now being proposed for young people with gender dysphoria.

And the recent change in the UK government, from a Conservative majority to a centre-left Labour majority, has done nothing to help this movement, it seems. The new Prime Minister Kier Starmer’s views on trans issues are inconsistent to say the least, and the new health secretary Wes Streeting is planning to uphold the ban on puberty blockers.

This new therapeutic model for gender-questioning young people goes by the name of ‘gender exploratory therapy’. But don’t be fooled by this seemingly harmless title: it’s plain-old conversion therapy, just under a different name.

Here’s what we know about conversion practises. Number one, they don’t work. Number two, they are strongly associated with an increased risk of depression, anxiety, and suicide. Number three, they tend to primarily target young people.

Conversion practises are also symptomatic of a society which discriminates against LGBT+ people, and this is something which comes and goes in waves. During times of societal stress and political instability, people look for a scapegoat, and trans people appear to be the popular whipping post at the moment. They’re a small marginal group which has been targeted because, quite frankly, they’re an easy target, and people can create a sensationalised narrative about them. It all feels very reminiscent of the things people have said to justify discrimination against gay people throughout the 20th Century. The arguments are the same: that it’s unnatural, that it’s a result of trauma, that it’s a threat to ordered society and the stability of the family. Same old, same old.

Gender exploratory therapy purports to be a neutral, non-judgemental approach to treating young people who are questioning their gender, using talk therapy, or psychotherapy, as its main method. However, when you look into the conceptual and narratological foundations of GET, some inconsistencies emerge.

First of all, it becomes immediately clear that the gender exploratory approach is predicated on an inherent distrust and scepticism of trans identities, a positioning of cisgender as the desirable default, and a treatment of gender transition as something which should be avoided if at all possible. It positions the therapist as antagonist, the arrogant parent who claims to know more about their child than the child themselves, whom the patient must overcome in order to access gender-affirming treatments. But, of course, the ultimate goal is for transition to not occur at all.

Proponents of this model are also proponents of theories of social contagion such as Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria (ROGE), as well as theories of trauma as the root cause of gender distress, and other explanations which pathologise trans identities. Therefore, the objective of GET is to ‘explore’ gender identity only to the extent that it delays transition until the patient has been suitably convinced to not go ahead with it. This hardly seems neutral to me.

Then there’s the matter of how similar the gender exploratory approach is to gay conversion practises.

Gay conversion practises have historically relied on the idea that being gay is a result of trauma. Sexual abuse or other adverse childhood experiences are frequently cited as the ‘cause’ of the homosexuality, and it’s believed that by dealing with these core traumas the homosexual feelings will naturally resolve themselves. Another common explanation is a disrupted relationship with the parents, particularly the father, which is believed to stunt the development of masculinity and inhibit a man’s natural heterosexual identity coming to fruition. Similarly, practitioners of gender exploratory therapy also believe that gender dysphoria in youth is the result of trauma, and the desire to transition is a way of dissociating from one’s natural, cisgender body. Both approaches assume that there is a normative cis/het identity beneath the gay/trans person waiting to reassert itself.

Both approaches also tend to appeal to biology as an argument that being gay or trans is ‘unnatural’. People against homosexuality have historically relied on the ‘man is designed for woman’ argument, while gender-critical people perceive ‘gender ideology’ as a threat to the sanctity of biological sex, implying that the body as it ‘naturally’ is should not be tampered with, and that being transgender is going against nature. (If we’re going to take that literally, why not stop taking all medication and ban plastic surgery while we’re at it?)

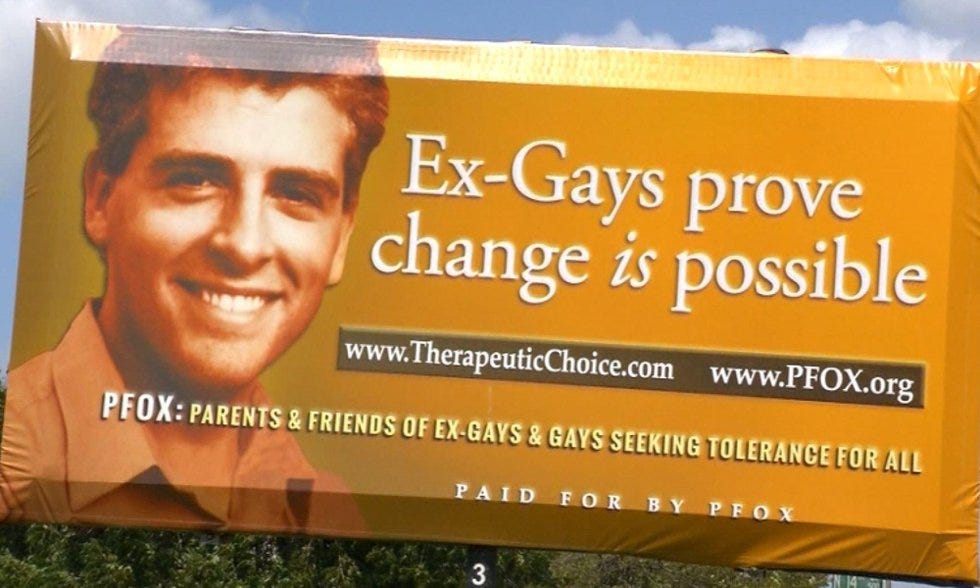

Then there’s the testimonials of ‘ex-gay’ patients, which are used as success stories by gay conversion practitioners to prove that their methods are sound and they work. Compare this with the stories of ‘detransitioners’, which are invoked by the gender critical movement as proof that gender-affirming care is damaging to young people. These stories are then used to push the agenda that gender-affirming care should be done away with altogether. There are differences between ex-gays and detransitioners, but the principle is the same: proponents of conversion therapy exploit these people’s stories to bolster their claims that gay affirmation, or trans affirmation, is wrong.

Both gay conversion therapy and gender exploratory therapy have great qualms about affirmation in general. Gay conversion therapists contrast their methods with ‘gay affirmative therapy’, which encourages the troubled homosexual to accept their sexuality, while gender exploratory therapists oppose gender-affirming care on the notion that it pressures children to transition and get surgery, despite the stats not backing this up. Indeed, it seems that most children diagnosed with gender dysphoria do not pursue medical treatment while they are young. But this false narrative of forced sterilisation and bodily mutilation is the only way that the gender exploratory model can exist — it has nothing to react against without it.

If you want chapter and verse on this stuff, you can read an article by Florence Ashley which goes through all of it, complete with citations and everything.

Or we could get it straight from the horse’s mouth. Joseph Nicolosi, considered one of the founders of gay conversion therapy, wrote a book in 1997 called Reparative Therapy of Male Homosexuality, and a quick read of what’s available from it on Google Books is very revealing. Of particular note is the fact that he does not call his model ‘conversion therapy’ but ‘reparative therapy’, which sounds much friendlier and more positive. In fact, Nicolosi himself states at the beginning of the book that his therapeutic model “is not a ‘cure’”, merely another option for the struggling homosexual. This is a dubious claim, as we will see.

What Nicolosi calls the “non-gay homosexual” – a man who struggles with homosexual feelings but does not identify as ‘gay’ – has been neglected by modern society, which has focused too much on affirmation and progress. He also wrings his hands about the fact that the move towards affirming homosexuality, rather than pathologising it, has stifled therapists who fear being labelled as homophobic (another parallel with gender exploratory therapists who mention the fear of being called transphobic), and has prevented them from “criticising the quality of the gay lifestyle”. Surprisingly, the book is not a polemic about how homosexuality is a blight on Planet Earth; on the contrary – Nicolosi has remarkable compassion for these men and wants to help them. But remember that much abuse is done under the guise of virtue.

Nicolosi devotes huge swathes of the book to analysing father-son relationships, with a particular emphasis on early experiences. Young boys’ relationships with their fathers which are thwarted, he believes, leads to homosexual feelings later on, which are a symptom of faulty development. The cause of the disrupted relationship might be an overbearing mother, or an emotionally distant father, or both. He laments the fact that so many young men are denied healthy relationships with other men, and, in his view, sexual relationships between men are just a misguided way of trying to repair the father-son bond. In other words, they’re just acting out.

To summarise, this guy had some major daddy issues. But don’t we all?

What seems clear, not only from gay conversion practitioners but also from their patients, is that a lot of this stuff is done with the best intentions. But, as the saying goes, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. And intentions are immaterial when the impacts of these practises are proven to be so harmful. The narrative that practitioners of GET perpetuate, that conversion practises are only practised by immoral, unethical people who want to eradicate queers, is incorrect. Conversion practises don’t just happen in the church basement; they also happen in the consulting room, with well-meaning professionals who purport to be ‘helping’ — that is, people like them.

I have no doubt that gender exploratory therapists also have the best intentions in what they’re doing. But at the same time, you can’t slap a smiley face on something and call it as such, when what lies deeper is something very different. While there are differences between gay reparative therapy and gender exploratory therapy, they are variations on the same theme. Regardless of its intentions, gender exploratory therapy has all the signs of conversion practises, and all the associated risks.

In order to protect young people from these conversion practises there needs to be a complete and unequivocal ban on them, one which is inclusive of practises targeting gender identity as well as sexual orientation. You might live in a place where it already is banned — in which case, good for you. But in the UK, where gender exploratory therapy was first developed, and which occupies an important strategic position in the debate around trans rights, conversion therapy is still legal. There needs to be accountability for health organisations in the UK, including the laudable UKCP, to prevent these practises from proliferating, and a ban on conversion therapy would provide a legal basis for this.

Tellingly, proponents of gender exploratory therapy oppose bans on conversion practises because they fear it would stifle their methods. Regardless, the record needs to be set straight that therapy is not a playground for the therapist to experiment with their own beliefs, or exercise their astute powers of critical thinking, but it is designed to serve the patient. And the patient gets to decide what is best for them. It’s their choice.