This article first appeared in Nouse, under the title “You Are What You Read: H is for Hawk”, in 2020. It has been reworked and expanded from its original form.

After the sudden news of her father’s death and the emotional fallout which ensues, Helen Macdonald decides, ostensibly on a whim, to purchase and train a goshawk. She has been dreaming of hawks, obsessed by them, and decides that getting one of her own is the necessary way to deal with her grief. Macdonald is an experienced falconer, this isn’t her first time training a bird - but she hasn’t flown hawks for years. Nevertheless, she drives up to Scotland with £800 with her to exchange it at a quayside for a goshawk. She names the hawk Mabel, and as she embarks on the intense and arduous ordeal of training a hawk, it becomes clear that her need to train this hawk is about more than just having something to do.

From childhood Macdonald had a fascination with hawks. She tells of how she used to sleep with her arms crossed behind her back, like wings. Other children had pictures of pop stars on their walls; she had pictures of kestrels. She took to falconry at an early age, going out into the fields with gruff, burly men who offered her snuff, and eventually she got a hawk of her own.

For Macdonald, hawks represented everything wild and ruthless about nature. They were bloody, beastly creatures, highly-strung predators; they were everything humans were not. The received wisdom from falconers was that goshawks were particularly difficult to train, due to their especially brutal natures - Macdonald describes them as “the Christopher Walkens of the bird world”. So when she found herself in an ocean of grief, the goshawk was the way out. Hawks live in the eternal present, unfettered by human emotions or regrets. They hunt, they kill, they eat, they sleep. Getting a hawk was the perfect way to run away from herself.

To call H is for Hawk a memoir is somewhat reductive. Yes, it is autobiographical, but it also blends various genres seamlessly and is something of a hybrid: it is at once memoir, literary non-fiction, natural history, a guide to the English landscape, an instruction manual for training a hawk, a glossary of falconry jargon, and a biography of the author T. H. White, whose fractious, tragic relationship with his own goshawk is intertwined with Macdonald’s journey with Mabel. These disparate strands of narrative are woven together throughout the book, each shedding light on the others.

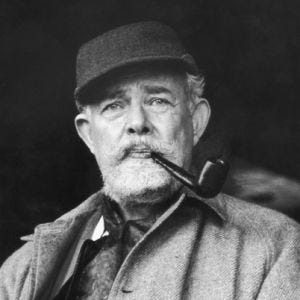

T. H. White, author of the book series The Once and Future King, reworkings of Arthurian legend, was born in 1906 in Bombay (now Mumbai). White had a troubled childhood - his father was an abusive alcoholic, and his mother was distant and cold towards him. He studied English at Cambridge and then taught at Stowe School in Buckinghamshire, during which time he published his first novels. Eventually he left Stowe School, retiring to a nearby cottage where he wrote the first book of the Once and Future King series, The Sword in the Stone, and, for a brief spell, trained a goshawk. His account of the doomed process of training ‘Gos’ is detailed in his 1951 book The Goshawk.

White struggled his whole life with shame around his latent homosexuality and sadistic desires - homosexuality was not decriminalised in the UK until after his death, in 1967 - and during his last years as a schoolmaster, his feelings which he could not find a way to express were becoming intolerable for him. After leaving Stowe, he retreated to his isolated cottage and cut himself off from society entirely. He decided to train a goshawk as a way to connect with the aggressive, wild side of himself not permitted in polite society, and, interestingly, he appears to project his own homosexuality onto the hawk. White loved Gos, but he also treated the hawk terribly and clearly did not know how to train one properly. The Goshawk chronicles this excruciating process as a kind of war between man and hawk, and eventually Gos breaks free and flies off into the wild.

Macdonald is haunted by White throughout her training of Mabel, having read The Goshawk as a child, because their motivations for training their birds were similar - they both retreated from the world of people and immersed themselves in the world of their hawks. Their hawks were reflections of who they wish they could have been: without feeling, uncomplex, safe. Both of them used their hawks to run away from their problems: White from his unresolved sexuality and his loneliness, and Macdonald from her grief.

Falconry is one of the oldest relationships between humans and other animals in existence (apart from where the animal gets eaten) and it is one of the last remaining ways that humans can legally interact with wild animals in such close proximity. Originating in Central Asia around 2,000 BCE and spreading to Europe in the Common Era, the practice of falconry was a symbol of wealth and prestige among the elite classes. Having a falcon or a hawk on your arm was said to signify nobility and mastery over wild things. Nowadays it is mostly practised by bird enthusiasts and naturalists, though it still retains vestiges of this elitism, particularly in its attitudes towards women which emerged in the 18th and 19th centuries. Falconry came to be perceived as a boy’s sport in accordance with the masculinisation of the outdoors and the feminisation of the domestic during this time, and male falconers referred to their birds in similar terms to how they might have viewed women. Goshawks in particular had a reputation for being especially difficult - prone to erratic moods, “flighty and hysterical”, fickle and changeable. Sound familiar?

As Macdonald gets to know Mabel, she realises that her preconceptions about goshawks were all wrong. The hawk is much calmer than she anticipated, and, as she later recalls, her strongest memory of Mabel is her playing. Viewing these birds as just cold-blooded killing machines isn’t telling the whole story.

That being said, the grisly realities of hawking are not shied away from in this book - Macdonald describes with vivid detail such necessities of the sport as giving the coup de grâce to a wounded rabbit, or getting goshawk talons to the head. It seems that it was this grisliness that she was after. She wanted to escape from the human world by entering the world of the hawk, viewing the landscape through the eyes of a predator. Macdonald describes how taking Mabel out hunting for the first time completely transformed her perspective on time and landscape - she no longer sorted everything into hierarchies, as naturalists are conditioned to do, but everything, from the ants to the houses, acquired equal importance, equal weight. Time slowed down to the point where hours felt like years. She no longer identified things with the names she had learned from a lifetime’s relationship with nature; everything was “patterns of light and shade and colour”. It was an addicting experience. It took her so far away from herself and her gnawing grief that it became the only place she wanted to be.

This is where things took a very dark turn. In the process of taking Mabel out hunting every day, as is expected with goshawks, Macdonald inevitably had to put a lot of animals out of their misery, maimed or else fatally injured by the hawk, so as not to prolong their suffering. (There were some inadvertent pheasant poachings.) The weight of these deaths were not lost on her, and she felt an enormous responsibility for the deaths of these animals. It was the only time she felt human.

She started waking up with her pillowcase damp, not knowing why. At the time, she thought it was allergies or perhaps an infection - in reality she had been crying all night. She started flinching in panic when the postman came to the door. She avoided people, cancelled engagements. There is constant mirroring throughout the book between Macdonald and Mabel – the hawk’s distrust of people and her bouts of irrational anger, both of them eating the game caught on their hunting trips, the hawk’s flights into the woods and her flights into the world of the hawk, seeing the world through its eyes. She wanted to become the hawk. And she was becoming one, in a way. But it was not without cost.

Macdonald relays a tale in the book via anthropologist Rane Willerslev about a reindeer herder in Siberia who follows a herd of reindeer for days, observing them intently, immersed in their world. Eventually he infiltrates the group and becomes part of the herd. The reindeer give him lichen to eat. He starts forgetting details about his human life - he has a wife, but he can’t remember her name. Once he realises what is happening, that he is becoming a reindeer, he flees in terror.

By ‘becoming a reindeer’ I don’t mean a werewolf-style physical metamorphosis, but a psychological one - a kind of trans-species psychosis, an annihilation of the human soul. There is something seductive about over-identifying with an animal. They seem so free, so unfettered by the quotidian human problems we have to deal with. If you want to be something other than human badly enough, you can in a way enact it, by banishing all of your human emotions to the unconscious.

It is only at her father’s memorial service that Macdonald realises her mistake: that by immersing herself in the world of the hawk, she has forgotten what it means to be human. That by pushing away her grief, she has also pushed away love and affection. She realises this after seeing how many people have come to remember her father, how many people he knew and had an impact on.

Grief is the price we pay for love. They are the two sides of the same coin; neither can exist without the other. After this revelation Macdonald seeks help and gets a diagnosis of depression, and from there truly starts to recover. She describes the moment where she knew she was going to be okay - while flying Mabel, she would check the sky every morning to ascertain what the weather might be like that day - precipitation, wind direction, atmospheric pressure, etc. Then one day she looks out at the sky and thinks, that’s really beautiful.

The story of H is for Hawk is a journey of going to the underworld and back. It is an archetypal journey which has shown up throughout mythology and literature since antiquity, where the Ancient Greek word katabasis meant a journey to the underworld. The most famous example of the underworld myth is the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice, in which Orpheus journeys to the realm of Hades, after Eurydice dies from a snake bite on their wedding day, in an effort to bring her back.

The underworld journey can be read in psychological terms as a descent into the land of the dead in the psyche, from which the individual returns spiritually transformed. In this book, Macdonald’s psychological underworld is the labyrinth of her grief. She journeys to the depths of her unconscious, nearly loses her way, and comes back alive. Crucially, she is not alone: she has a hawk by her side. Every hero in their underworld journey has some kind of charm to aid them - the underworld in Ancient Greek mythology has the god Hermes as the soul-guide (psychopompos) between the living world and the world of the dead - and the hawk is this talisman, the carrier of the numinous, who accompanies her there and back again. Interestingly, birds are one of the most common images of animals as psychopomps, and it’s clear to see why: their ability to fly, combined with their pan-cultural associations with both death and life, make them appropriate carriers of this archetype.

In a scene towards the end of the book, Macdonald visits T. H. White’s Buckinghamshire cottage, a pilgrimage of sorts - the cottage where he trained his goshawk. She sees a man kneeling in the garden, and for a brief instant she is convinced that the man is Mr. White himself. In a reverie, she imagines what it would be like to get to know the man who is not T. H. White but might know something about him, to learn more about her long-since-dead falconer spirit-companion, to bring him back somehow. But then she stops, and decides to release that desire, to let it go. And in so doing, she feels immense relief.

This is the main lesson of the book: that there is more to the world than what we project onto it. Humans have a natural proclivity for viewing the natural world as a mirror of ourselves. This can lead to a great love and appreciation of nature, but it can also have troubling consequences. Separating ourselves from nature and viewing it as a blank slate onto which we can project our own desires, rather than a place to which we belong, with its own life, its own value, has an isolating effect on humanity, and also justifies exploitative behaviour which has driven the ecological crisis we now face. Eventually Macdonald comes to love Mabel not because she wants to become a hawk but because they are so different, so unalike.

If we want wildness - and it has been all but erased in modern society - instead of outsourcing it through a hawk, or through destroying forests and habitats, we can turn inward and realise that the wildness we seek is within, it lives inside of us. Ultimately, we are part of nature: we are nature itself, we are not separate from it. Coming into reciprocity with the natural world, and claiming our responsibility to it, is a crucial part of moving beyond our projections - what Macdonald calls “learning to love difference”.