The Colonial Mentality

where does it come from?

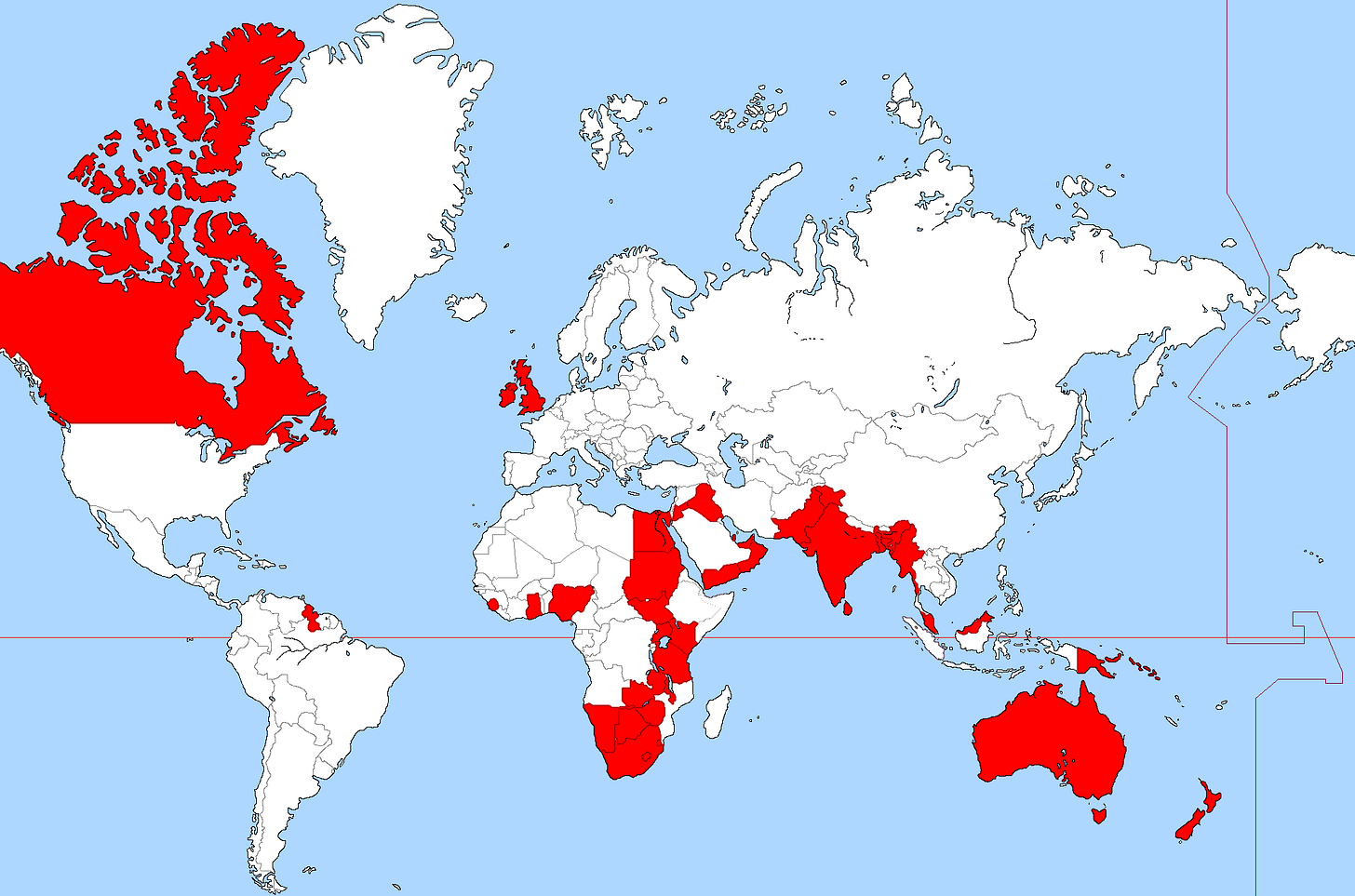

As a person who grew up in Britain, the concept of empire has been important to my life whether I like it or not. The British Empire has had a huge impact on the planet in the last few centuries—it invaded nearly every corner of the globe, and played a pivotal role in the globalisation of trade and commerce. It currently is still the largest empire in terms of land area that has ever existed. Some of the effects of this have been good—the spread of liberal democracy, cultural exchange, allyship between countries—and other effects have been not so good—slavery, the decimation of Indigenous populations through war and spread of disease, loss of Indigenous languages and traditions. Vestiges of this colonial past still exist today: the Commonwealth, for instance, still gives Britain sovereign power in a number of countries, though these countries are politically independent and gradually gaining self-sovereignty; and many of the territories Britain once controlled still have predominantly settler populations.

For context, it would probably be helpful to provide a brief history of how the British Empire came to be. The British Empire started out with just the English, who colonised Ireland in the 16th century. At this point, Portugal and Spain had already established colonies in the Americas and in Africa, and England was getting wind of this; they were becoming a bit jealous, wanting some of these exotic faraway lands for themselves. The English began to explore North America, and after some failed attempts, they established their first colony in Jamestown, Virginia in 1607. These colonies then expanded down the east coast and up into Canada. They became safe havens for people fleeing religious persecution, as well as places where convicted criminals were sent. Then the English went to the Caribbean, and started the slave trade between Africa, the Caribbean, and their North American colonies. In 1707, Scotland and Wales joined forces with England to form Great Britain.

Over the course of the 18th century, Britain would gain a lot of territory from other competing European Colonies, most notably after the Seven Year’s War, when the French ceded the entirety of New France to them. They also gained Florida from the Spanish, and now controlled all of North America east of the Mississippi. Shortly thereafter, however, tensions erupted in the American colonies, and the American Revolution led to their independence from the British. As a result of this, the empire turned its attention away from North America and towards Asia and Oceania. They claimed Australia and New Zealand, as well as a number of island nations in the vicinity. On the other side of the Pacific, they were also making progress in western Canada, setting up colonies in British Columbia. The British again gained territory after the Napoleonic Wars from the French, the Spanish, and the Dutch.

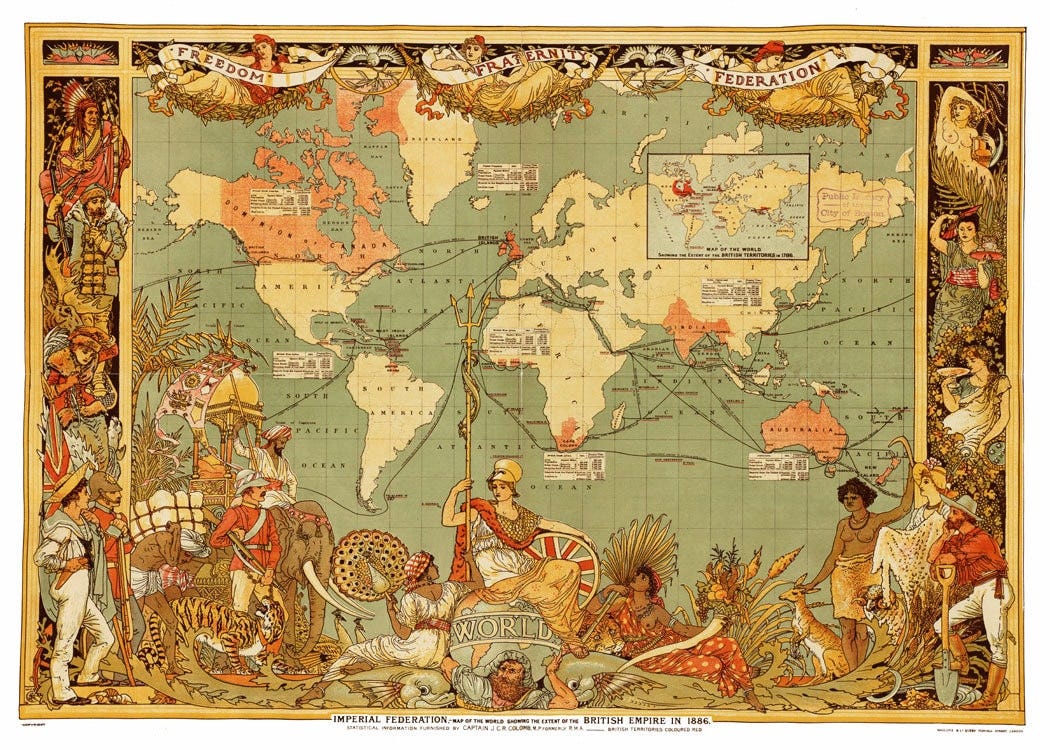

The 19th century was one of global dominance for the British. As the most powerful empire they remained unchallenged globally, and gained more territory in South Asia and Africa. The onset of the Industrial Revolution meant that slavery had become less important to the British economy, so, after rebellions and abolitionist movements intensified, slavery was abolished.

By the start of the 20th century, Germany had become a rival power, and this period of relative peace ended with the start of World War I. After the war, Britain gained territory in the Middle East and Africa from the Germans and the Turkish Ottoman Empire, which had by then dissolved. This was the peak of the British Empire’s territorial control—13.7 million square miles, or 24% of the Earth’s total land area.

After 1921, Britain began to grant independent statehood to their territories. The Dominions of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Newfoundland, and South Africa became autonomous countries in 1926. Britain lost their grip on many of their Asian territories during World War II, and shortly after that, the British Raj ended and they withdrew from India. They also pulled out of the Middle East and, later, the African colonies. With the decline of the British Empire, the United States, Russia, and China emerged as the world’s dominant powers, positions which they still maintain today.

It’s rather uncool to be a British person these days. As we grapple with the legacy of the British Empire and the harm it has caused, being from here can come with a sense of guilt by association. The effects of Britain’s maltreatment of Indigenous peoples are all still in very recent memory: to take just one example, the podcast series Stolen: Surviving St. Michael's investigates the impact on one family of a residential school in rural Saskatchewan, Canada and the abuses that went on there. Such residential schools were set up across Canada and the United States, and they aimed to force Indigenous children to assimilate into white culture by separating them from their families and forbidding them to speak their languages or practise their cultural traditions. Verbal, physical, and sexual abuse was widespread. Many of the people who went to these residential schools are still alive today, as are many of the people who taught at them. The last one closed in 1996.

But it has to be said—Britain isn’t the only country to have invaded other places, or forced Indigenous peoples off their ancestral lands, or enslaved people. Much of Central and South America was colonised by the Spanish or the Portuguese, and other European colonies, such as French and Dutch, existed alongside British ones, though most of these territories were eventually ceded to the British. Slavery has been around almost as long as people have. Not to mention other empires which have existed through history, such as the Ottoman or the Japanese, as well as present-day conflicts, such as in the Ukraine, far-west China, and Palestine, which echo imperialist struggles of the past.

The decolonisation movement has gained a lot of traction in recent years, fuelled by Black Lives Matter protests and the increasing awareness of the plight of Indigenous peoples worldwide through the internet. Just this year, military coups have taken place in a number of West African countries, partly due to frustration with French colonial influence, replacing democratically elected leaders with militant groups. New initiatives are being set up to ‘decolonise the curriculum’ and make media more diverse. But decolonisation has in fact been happening gradually since the mid-20th century, when the British started to pull out of their colonies in Africa and the Middle East. The decolonisation movement these days is taking it even further, interrogating how Britain’s colonial history has impacted how we teach in our educational institutions, and examining how we might benefit from diversifying our models of understanding the world.

It has also become unfashionable, at least in some areas of the public discourse, to show a historical interest in the British Empire at all. According to some people, we are not allowed to even talk about it anymore, unless it’s specifically about what an evil blot on humanity it was and how all white people are colonisers. We are not allowed to think critically about it, but must condemn it or else. This kind of rhetoric is divisive and doesn't actually help us understand how the empire operated, what the effects of that were, and what we might do differently going forward. In fact, learning about the British Empire can further confirm a view of it as a highly questionable endeavour. We need not be afraid of history, and to deny it not only ignores suffering that deserves to be recognised but sets up the cycle to repeat again in the future. If we do not learn from our mistakes, we are doomed to repeat them.

So—given that people, across the globe and throughout time, have displayed this proclivity for invading and exploiting foreign territories, we might ask: Where does this impulse come from? Where in the psyche does it originate? And what is its true aim? My proposition is that the colonial mentality arises not from the desire to persecute others, though that often happens, but from an innate desire to explore, innovate, break new ground, prevent stagnation, and stave off decline, i.e. death. The conquering of new territory in the physical world functions as a substitute for claiming new psychic territory—that is, discovering previously unknown parts of oneself which aids individual development—a substitute which is never satisfactory. Therefore, empires expand and expand, claiming more and more territory, like Sisyphus rolling the boulder up the hill, hoping that once they conquer the world they will finally be satisfied. But it’s never enough. And once you get land, you only become afraid of losing it.

People tend to be dissatisfied with what they have. They find the routines of life boring and repetitious, or perhaps they’re troubled by the country or the circumstances in which they live. The solution, they think, is to go somewhere else, find another place that will fix them somehow, rather than investigate where the deeper root of their inner disquiet might lie, and consider what can be done about it here and now. 16th- and 17th-century Britain was beset by war and disease, ruled by tyrannical monarchs, sexually repressed—and what better solution than to go to some exotic place where people were more free and liberated? This mentality can operate on both the personal and the collective level, and it is still alive and well today—the tourism industry is huge, bigger than it has ever been, and it sells us the seductive fantasy of escaping our boring quotidian existence for a few short weeks, or even just a weekend, and immersing ourselves in a foreign place in the hope that we will find rest and renewal there. It’s all well and good to be curious about the world, but where is the line between what you have projected onto a place and what it actually is? Perhaps it’s impossible to delineate that line. But we should nonetheless be careful not to fall prey to exoticism.

Look at any world map, and three countries immediately jump out as among the biggest ones: Canada, the United States, and Australia. Much of Canada more than a hundred miles from the US border is wilderness, populated only by small communities, and sparsely at that. Australia is mostly desert. The United States is more densely populated, but still has vast areas of wilderness, particularly in the northern forests and the deserts of the south-west. Huge swathes of the US and Canada are former British colonies; Canada and Australia are still part of the Commonwealth. Now look at the United Kingdom—conveniently placed in the centre of the map, but rather diminutive and small by comparison. To put it in perspective: England, Scotland, and Wales can fit into most of the larger Canadian provinces and territories many times over, as well as many of the 50 US states.

It’s clear what the Brits’ intentions were when expanding their Empire: they wanted something bigger. They wanted to take up as much of the world map as they could, plumb the land for resources, and make themselves eternally rich and famous. Remember that Spain and Portugal established colonies in the Americas long before the British, and competitive jealousy was their main impetus for crossing the Atlantic in the first place. They weren’t satisfied with what they had.

But were their endeavours successful? Maybe so. The US and Canada, as well as Australia and New Zealand, are still predominantly populated by settlers, and a large proportion of them trace their ancestry back to Britain. Many people came over from Europe, made their homes there, and led happy lives. But it can’t be ignored that these countries were built on war, genocide, and slavery. A lot of unnecessary suffering was involved. And the effects of this are still deeply felt in Indigenous communities today.

Earlier this year, the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh returned a totem pole to the Nisga’a Nation, an Indigenous community in British Columbia, after it was taken without permission by an ethnographer in 1929. The totem pole was shipped over by plane and restored to its original place in the village, a process which has been dubbed ‘rematriation’, the feminine counterpart to repatriation, owing to the fact that the Nisga’a Nation is a matrilineal society. It was a watershed moment for British museums, which are still full of stolen artefacts. The totem pole is the first item to be returned in this way from a British museum, and it paves the way for more to come.

Other reparations are being made as well. Places are having Indigenous names restored to them, such as the Haida Gwaii archipelago off the west coast of Canada, formerly known as the Queen Charlotte Islands, as well as people in New Zealand increasingly referring to the country by the Māori name Aotearoa; financial donations are being made; people are acknowledging the land on which they live and work as ceded Indigenous territory, naming the tribes who occupied the land before European settlers arrived. This is a heartening change of direction; long may it continue. We cannot change history, but if we acknowledge the harm that has been caused and work collectively towards equality and justice, the future can be better than the past. And maybe we can start investing in the places where we actually live, rather than always looking somewhere else for answers.

Nice job, Jack, a good overview, very well-written and well balanced. I like your theory of the colonial 'mentality' as it locates it in impulses and motives that naturally human and that anyone can understand. As a Canadian living in British Columbia myself, I am well aware of how Britain's colonization has impacted social and political realities in Canada. Generally, the history has been tragic for indigenous peoples in Canada. One small point I'll make about that. You refer to the majority of Canadians in Canada today as 'settlers'. That's a loaded term politically as it has only come into use recently to describe some Canadians, whose ancestors did literally settle, but whose descendants (such as myself) actually did not. Again literally, being born here, I am a 'native' of this country, and to boot our national anthem begins with the words, 'O Canada, our home and native land', a unifying message. Unfortunately, in my view, that message is rejected by some with an agenda to divide rather than unite the country. Some indigenous Canadians I've spoken to also reject the term when applied to people today. I think they have the right idea. Anyway, thanks for the read.