Yes, the hype is real: St. Vincent’s new album, All Born Screaming, is bloody brilliant. This is not a review of the album, but suffice it to say that it’s her boldest, most uncompromising statement yet. It’s deep, dark, intense, and the production is immaculate. The album is ethereal and earthy, caressing and punishing, gentle and harsh by turns.

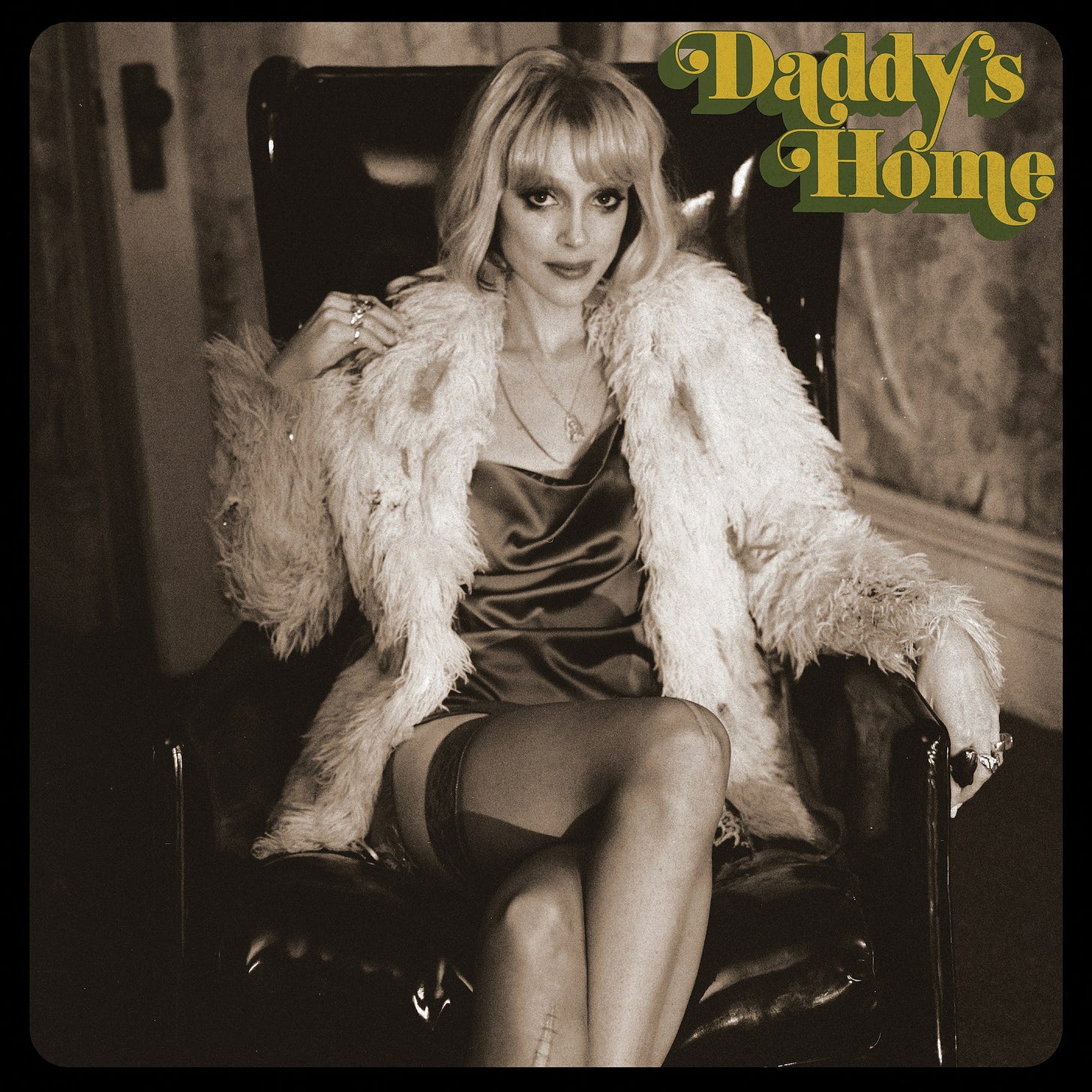

But something that keeps bugging me as I read the reviews is the weird and unnecessary comparisons to her previous album, Daddy’s Home. Daddy’s Home, it appears, has come to be viewed as the one rare misstep in her career – which is news to me, because I thought the album was wonderful, certainly among my favourites in the St. Vincent catalogue. Its warm sepia tones, 70s feel, and complex yet palpably listenable musical compositions make it one of her more compelling albums in my opinion. And I know I’m not the only one who thinks this. So why has it come to be the black sheep of her discography?

For starters, if you’re not familiar with the work of St. Vincent, here’s the quick run-down. St. Vincent is the alias of singer-songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, and producer Annie Clark, born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and raised in Dallas, Texas. She cut her teeth as a musician on tour with The Polyphonic Spree, and later with Sufjan Stevens. She released her first album, Marry Me, in 2007, and has gone on to release a string of albums considered some of the finest in the art-rock genre, such as Strange Mercy, the self-titled St. Vincent, and MASSEDUCTION. Clark is particularly notable for her innovative guitar playing, which combines harsh, gritty distortion with a sophisticated jazz vocabulary.

One of the defining characteristics of her career is the fact that she has historically assumed a persona for each album. Strange Mercy was the “housewife on barbiturates”, St. Vincent a “near-future cult leader”, MASSEDUCTION the “dominatrix at the mental institution”, and Daddy’s Home a blonde-wigged 70s starlet à la Candy Darling.

On Daddy’s Home in particular, this assumption of a persona attracted criticism where Clark had previously received praise. Critics felt – and this is the Pitchfork milieu of music criticism, not the general populous – that the persona detracted somewhat from the music and was on the whole rather irritating. In other words, they felt that the whole persona thing had gone too far, and they wanted to see the “real” St. Vincent, or the real Annie Clark. This is partly because much of the narrative which has been created around Daddy’s Home was that it was ‘a personal album’, even “her most personal record to date”, making particular reference to her father’s incarceration, which is the subject of the title track. But if you look at the album in detail, you’ll find that’s really as personal as it gets. The rest of the songs are about different characters and their situations – Clark describes them as “short stories”.

(My theory is that it was the wig that bothered people more than anything else – the actual physical manifestation of persona in covering up one’s ‘natural’ hair, a step further than the accepted practise of changing one’s clothes or fashion style, or even dying one’s hair, seems to have been too much of a confrontation for some.)

All Born Screaming, on the other hand, would appear to be without persona altogether. Much of the praise that has been lavished upon the album has to do with the perception that Clark has ditched her tiresome personae in favour of something more ‘real’, more ‘natural’. “Replacing alter egos with raw immediacy”, reads one review in The Guardian. Pitchfork calls the album “a hard reset on the St. Vincent project”. Indeed, Clark herself has stated that this time around she didn’t want a persona, and calls the album “the sound of the inside of [her] head”.

Vulnerability has become something of a commodity in the culture of today, no doubt as a reaction to the stiff-upper-lip, keep-your-feelings-hidden modus operandi of decades past. People bare their souls online, sending out their every thought into the digital ether, and are praised for it. And like all commodities, people want more and more of it; we are expected to mine our vulnerabilities for profit in the form of clout or likes and followers. Conversely, people who are more guarded or less forthcoming with their feelings in public are regarded as cagey and suspicious. The very word persona now carries associations of duplicitousness, lies and deceit, like it’s a calculated, evil plot to be misleading. And that’s not exactly incorrect, not entirely. But the nature of persona, in the psychological view, is that we perform it even when we are not aware that we’re doing so.

The concept of persona as we now know it originated with the psychoanalyst Carl Jung. He conceived of persona as the part of the psyche which mediates between the individual and society, functioning as a protective barrier against the expectations and judgements of other people, keeping the soul, what lies beneath the surface of the ego-personality, intact. However, the persona is also a natural and necessary part of us — it would be impossible to move through the world and interact with other people without the persona.

Some people like to think that they have no ego, no persona at all; they’re raw and real and genuine at all times. Other people are too entrenched in their persona, too rigid, completely unable to open up their deeper selves to anyone. The distinction between these two is narrower than you might think. Crucially, the persona needs to be flexible – it needs to allow room for the soul to shine through the cracks (and every persona has its cracks) at the appropriate moments. It can’t be a complete brick wall: it needs to offer the right amount of protection and nothing more. The persona is what is projected outwards, it is a compromise; when it turns inwards it becomes destructive.

Coming back to St. Vincent, then: One of the reasons some critics were disappointed with Daddy’s Home was that they felt the persona obscured what could otherwise have been a personal, vulnerable album. I’ve already said that this is a false narrative, but what it also fails to understand is that the very act of writing a song and performing it, no matter what it’s about – indeed, any artistic act, regardless of medium – is, as the kids say, super vulnerable. When you offer the thing you have created to the public, you open yourself up to criticism, and that takes courage. The critics are now delighted with All Born Screaming because it carries the performance of no persona, which fits perfectly into their narrative of people ‘finding themselves’ and becoming perfectly un-fake. It’s a compelling narrative, but it ultimately falls short of the truth. And as we have established, there is no such thing as no persona. Having no persona is in itself a persona, albeit one that denies itself in a contradictory catch-22. You see how this gets quite complicated quite quickly.

One review of Daddy’s Home compares it rather unfavourably to the title track from Strange Mercy, which in retrospect deals with a lot of the same subject matter and life events as the former, though at the time of its release the stories behind the songs were still a secret, before they were forced into the public eye by journalists. Strange Mercy is indeed a very personal album, perhaps her most personal; but, bizarrely, the reviewer has a kind of nostalgic pining for that song and how supposedly unguarded it was — even though Strange Mercy and Daddy’s Home are completely different albums, made at different points in time, with completely different goals, influences, and ideas. Not only that, but Strange Mercy was the start of St. Vincent’s persona era proper, and she remained completely mum on what the songs were about at the time. Having a persona actually allows you to reveal all in your work without feeling like you’re completely exposed.

Another crucial point people keep forgetting is that, for Clark, the music always comes first. She creates the music, and then she overlays a visual identity and a persona on top of it, because it’s fun, and because it’s how music is marketed and displayed these days. Every album needs an album cover and promotional art, and usually there are music videos as well. So why not self-consciously invent a persona for the performance that you are already doing?

But, it seems, these personae are a thing of the past for Clark, at least for now. No-one knows what she will do next: if she will continue in this vein, or if she will decide she wants to try on another hat for the next album. Her unpredictability is part of what makes her such an exciting artist.

I want to round off this discussion by drawing attention to something Clark has stated many times over the years. Music, like all art forms, is a subjective experience, and a song will be interpreted differently by every person who listens to it. Clark is very much a believer in allowing the listener their own interpretation of her songs, not imposing her view of them as the author onto the person listening. She recognises that her relationship with the music she loves is highly personal and sacrosanct, and that sometimes, having the artist state what their song is about can have a negative impact on her experience of it. She puts it this way: “I don’t give a shit what the artist was thinking! I care what it means to me.”

Works of art are a communication across time and space; they are not fixed or immutable. Once you put something out into the world, it doesn’t belong to you anymore, it belongs to the person who will receive it and treasure it as a gift. This exchange is the completion of the creative process: when the finished work arrives in the hands of the person who will bring their own experience to it and love it for what it means to them. Perhaps, instead of expecting people to perform vulnerability for us, we can trust that our experience of a song is what will ultimately remain, that it exists independently of anything else that can be attached to it, and that it is the most important thing about art.

You might also like:

The Tortured Poets Department

“‘Cause I’m a real tough kid / I can handle my shit”, sings Taylor Swift on the song “I Can Do It with a Broken Heart”, one of the more upbeat songs on her largely melancholic new album, The Tortured Poets Department. The song makes clear reference to her wildly successful run of concerts, the

This is brilliant Jack! I love St. Vincent, what a great breakdown of their work.

so very instructive. I started listening to the music as I read. Most insightful, thanks!