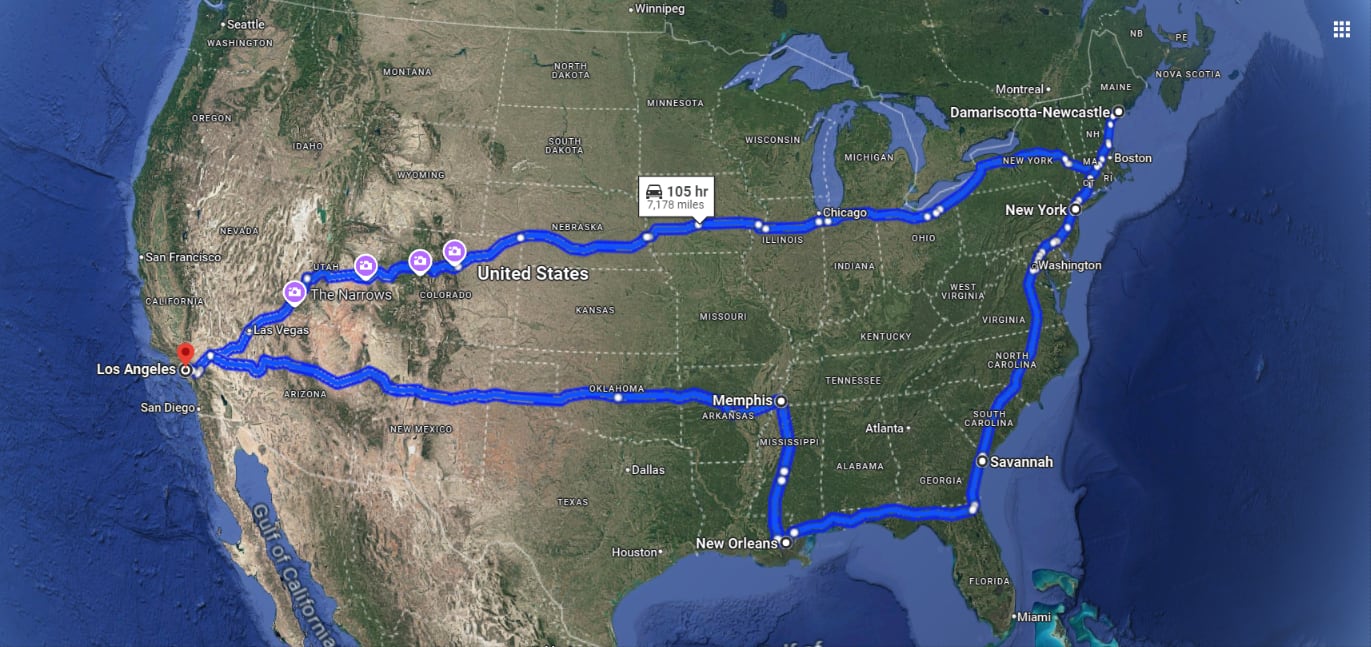

Mapping Joni Mitchell's 'Hejira'

the refuge of the roads

Hejira is Joni Mitchell’s eighth album, and the penultimate in the run of albums which make up her classics period – which some say begins with her first album, Song to a Seagull (1968), but I would argue actually begins with Ladies of the Canyon (1970), and ends with Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter (1977).

The album was written over a year of road tripping across the United States and Canada between 1975-6, both on tour with Bob Dylan and the Rolling Thunder Revue, and on her solo travels afterwards. Following the collapse of a relationship, a cancelled tour, and acquiring a tricky cocaine habit, Mitchell decided to hitch a ride with two guys she had met in Los Angeles for a cross-country road trip to the east coast in Maine. From there she went off on her own down the Atlantic seaboard to Florida, and then along the south coast back to California.

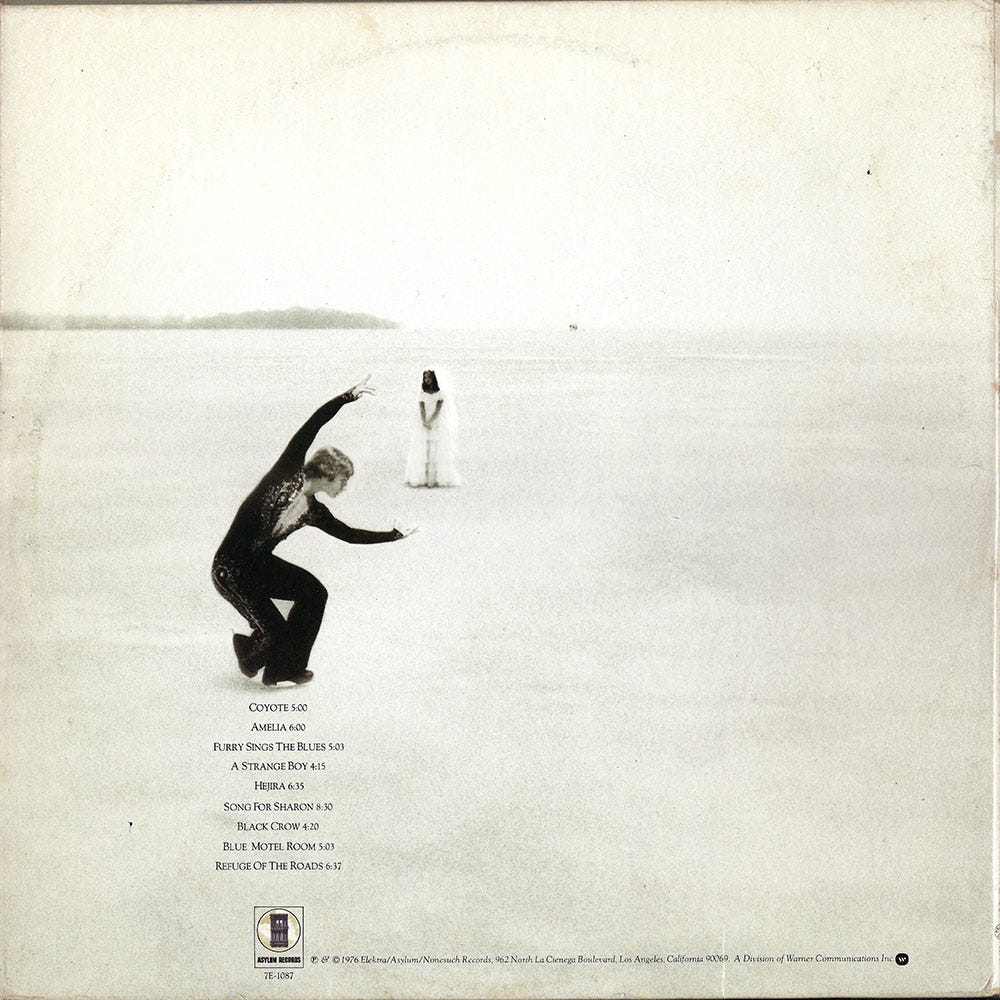

The Great American Road Trip is well-trodden ground in music and otherwise, but before the time of this album being written it was mainly the territory of men. Women had less freedom; it wasn’t an option for them to go off travelling on their own for months at a time. It probably wasn’t even safe. But by the time Mitchell’s career took off, the women’s movement was in full force, redefining and expanding the roles of women, and she was one of the first in a new generation of women travellers, inhabiting a decidedly masculine role while bringing her own experience as a woman to it. On the album cover, shot between a studio in Los Angeles and Lake Mendota, Wisconsin, she looks coolly into the camera in black garb, set against a backdrop of a wintry frozen lake with trees. The road spills out from inside her like a roll of carpet, as if she is a screen onto which it is projected.

The songs on Hejira are elliptical, deeply introspective, and largely eschew pop or folk song patterns, seeming to exist almost in their own universe. The title comes from an Arabic word referring to Muhammad’s flight from Mecca, and Mitchell interprets the word to mean “running away with honour”, adapting it to her situation. The album certainly uses the open road as a mirror of the psyche, wherein Mitchell interrogates her feelings about relationships, womanhood, and her commitment to her art.

Roads are everywhere on this album, and form the central motif as Mitchell wends her way from town to town and from state to state. Apart from the stuttering, rollicking “Black Crow”, all of the tracks make reference to specific locations, and landscape is a source of inspiration and existential isolation, reflecting her inner conflicts and throwing them into sharp relief. We meet a few characters along the way, but mostly she is alone, travelling, with only her thoughts for company.

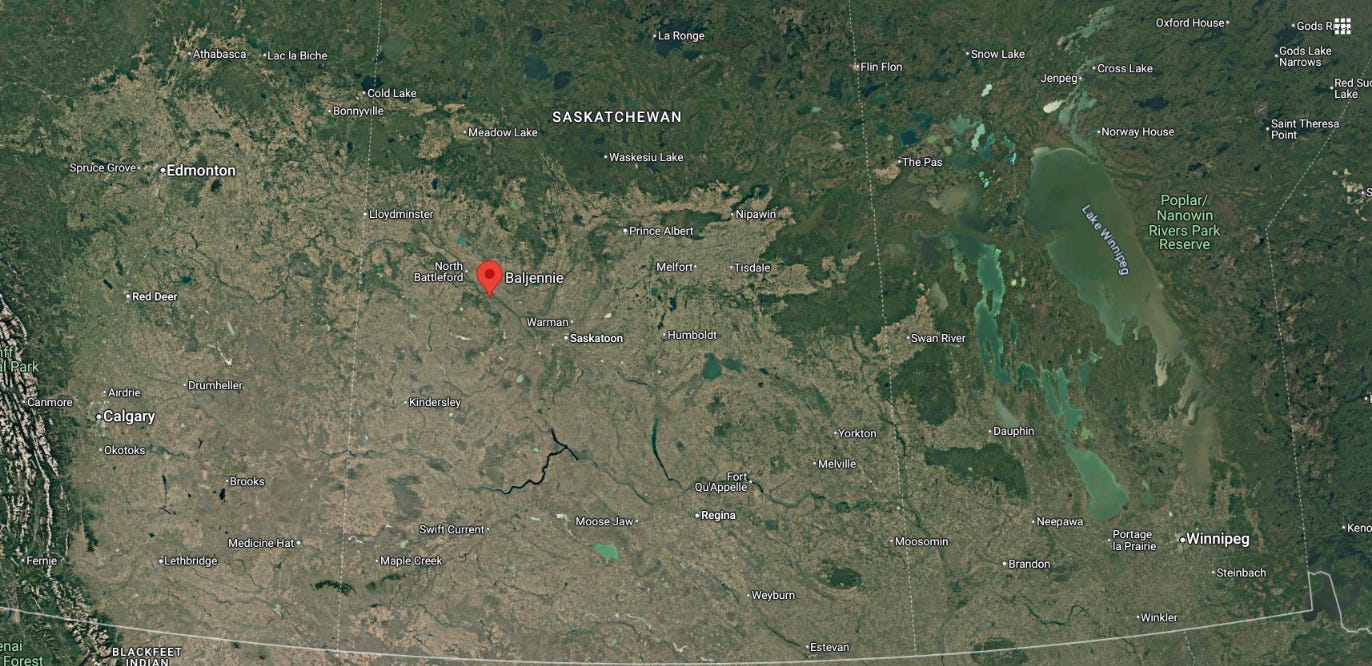

“Coyote”: Baljennie, Saskatchewan

We begin with the first song of the album. “Coyote” was written while on tour with the Rolling Thunder Revue, and details a fling with a man who would appear to be of the predator type. An early version of the song can be heard in a video where Mitchell performs it at Gordon Lightfoot’s home in Toronto alongside Bob Dylan. By the time Rolling Thunder got to Montreal the song was finished, and she debuted it there.

In the third verse, Mitchell recalls an encounter with a real coyote, “On the road to Baljennie / Near my old hometown”. Baljennie is a small hamlet in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, off Highway 16 between North Battleford and Saskatoon. Mitchell grew up in this area of Saskatchewan, and considers Saskatoon to be her hometown.

As the Rolling Thunder Revue’s Canadian dates were confined to the eastern part of the country, they would never have gone through Saskatchewan, so it appears this is a memory from Mitchell’s childhood. The song would probably have been written between Quebec and Ontario. Nonetheless, Baljennie is the only place name mentioned in the song, so Mitchell’s home turf gets a pin on the map.

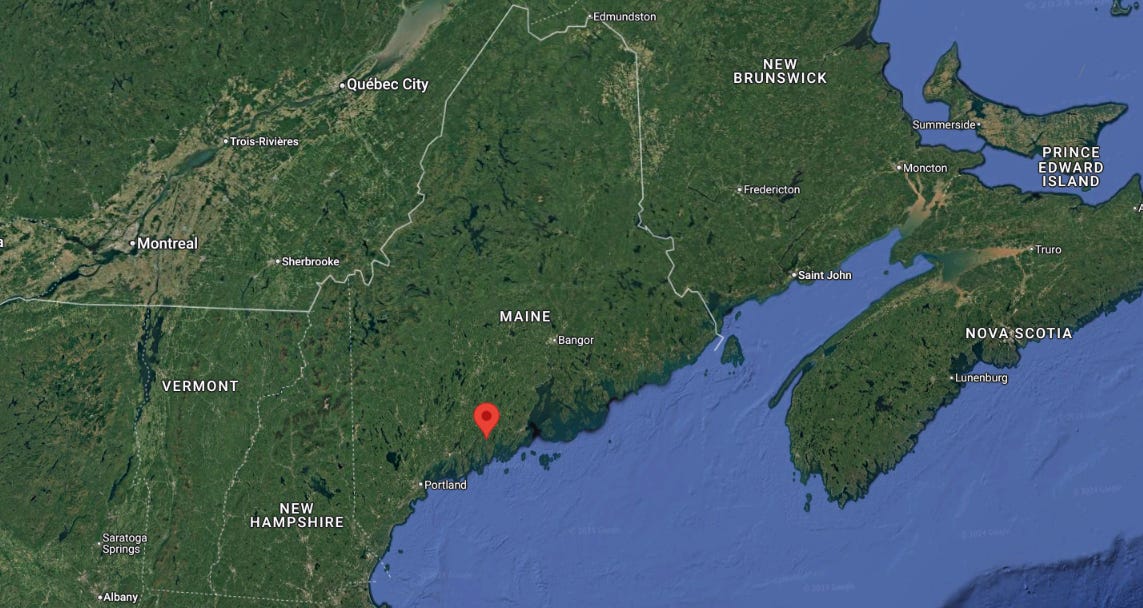

“A Strange Boy”: Damariscotta-Newcastle, Maine

The fourth track on Hejira recounts another affair, with one of the men she was travelling with on her initial jaunt from the west to the east coast. We know that their destination on this trip was the northeastern state of Maine, but the song doesn’t reveal exactly where in the state. Aside from when Mitchell finds an old piano among “waxed New England halls”, the only other clues are that we seem to be in a coastal location, as evidenced by the “surf rising” and the “parched ribs of sand” which would indicate a beach.

Some digging reveals that the trio ended up in the twin villages of Damariscotta-Newcastle, only a few kilometres from the coast. In fact, the very place where Mitchell played that old piano has been found to be the Newcastle Inn, complete with the dolls and everything. This is all according to the Maine music magazine Down East.

The dramatic, pensive title track “Hejira” also appears to take place around this area, what with the references to snow and “a man and a woman sitting on a rock”. The “pinewood trees” also situate us in the mixed pine-hemlock forests of New England. The Rolling Thunder Revue wrapped up in December, and Mitchell’s subsequent road trip happened shortly thereafter, so it would have been the dead of winter by the time she reached the east coast. It’s likely, though, that this track was written after Mitchell departed from her friends in Maine, as she is alone, pondering the troubles of romance, en route to her next destination.

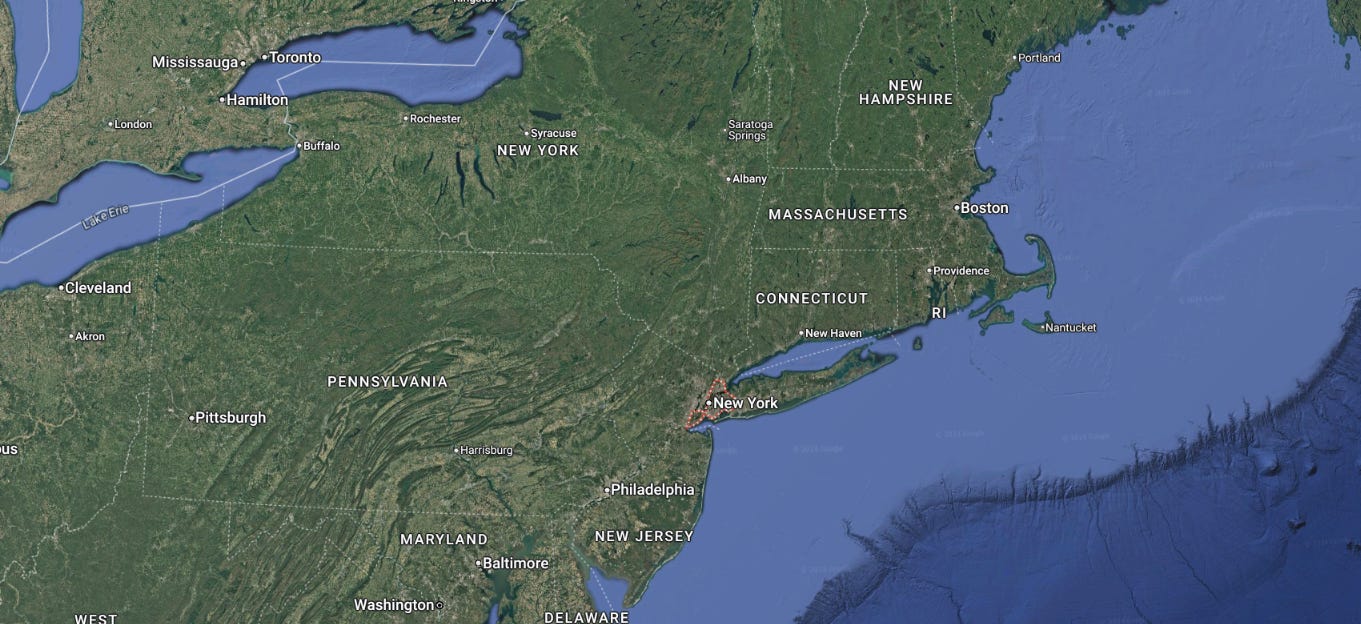

“Song for Sharon”: New York, New York

“Song for Sharon” opens on Staten Island. Mitchell is there to buy a mandolin (it’s been confirmed that she actually bought a Gibson K-4 mandocello, from the Mandolin Brothers store) and it’s the sight of a storefront mannequin wearing a wedding dress – “the long white dress of love” – which sets off her ruminations on love, marriage, and the path she has taken, an unconventional path for a woman even in the 1970s.

We then go on a tour of New York City, stopping on Bleecker Street for an ill-fated visit with a fortune teller, and also at Wollman Rink to watch the ice skaters. All the while Mitchell is reminiscing on her childhood and her idealised view of love.

The ‘Sharon’ to whom the song is addressed is a childhood friend of hers from Saskatchewan, and she represents the alternative path Mitchell could have taken, had she been more conventionally minded: the husband and the farm and so on. She contrasts between them, and the song thus becomes a comment on womanhood and the choices and sacrifices women have to make in their lives.

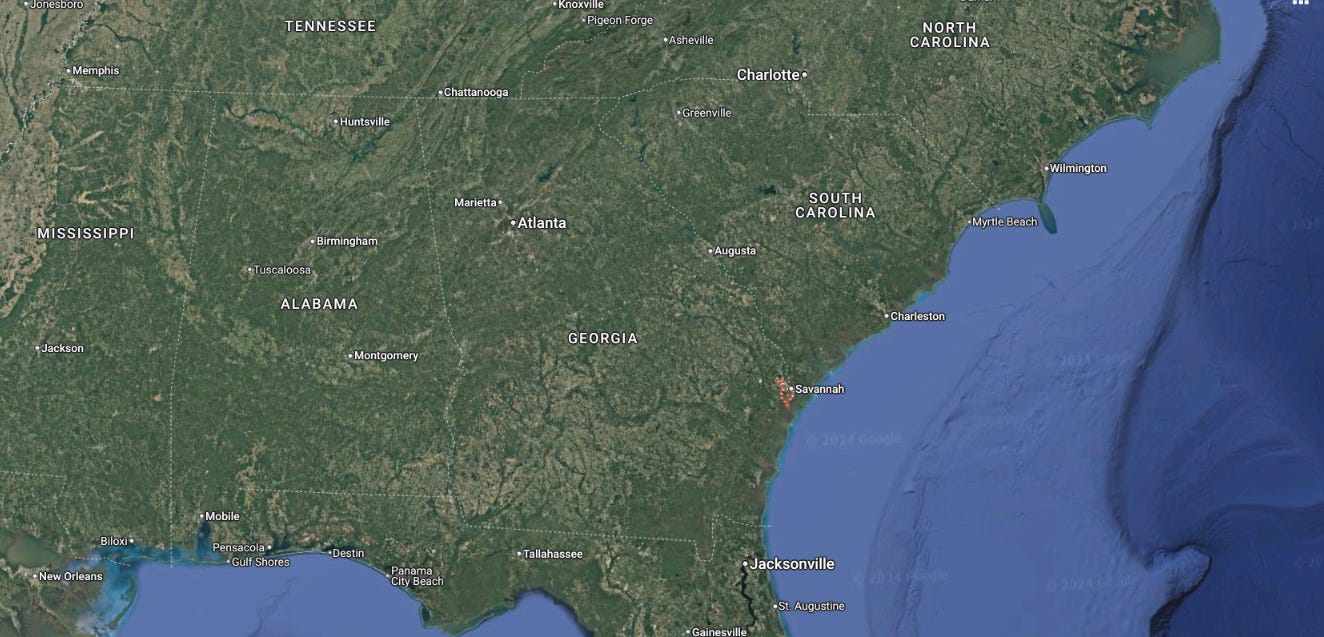

“Blue Motel Room”: Savannah, Georgia

Our next stop takes us to the Deep South: “Here in Savannah it’s pouring rain / Palm trees in the porch light like slick black cellophane”. Savannah is a city in the state of Georgia, at the border with South Carolina. By this point in her journey, Mitchell is wearing wigs and using fake names to disguise herself so she won’t be recognised. One of the things she is running away from on this Hejira of hers is the trappings of fame and excess, but it’s also a kind of annihilation of identity that she’s after.

In this song, Mitchell makes possibly the clearest statement on the whole album about the journey she’s on: “I’ve got road maps from two dozen states / I’ve got coast to coast just to contemplate”. The United States is a vast country, and the long hours spent on the road undoubtedly give you a lot of time to think, which is why it has long held such a fascination and a pull for people seeking a kind of spiritual enlightenment. Once again she is ruminating on love, particularly a person with whom she has had a difficult relationship. “Will you still love me / When I get back to town”, she sings in a languorous, smoky drawl.

We also get a real sense in this song that she’s writing these songs along her journey, while stopped off in motels and service stations. She’s not simply remembering a motel room; she’s in the motel room, and describing it to us in real time. This gives the album as a whole a sense of immediacy, like we’re really on the journey with her.

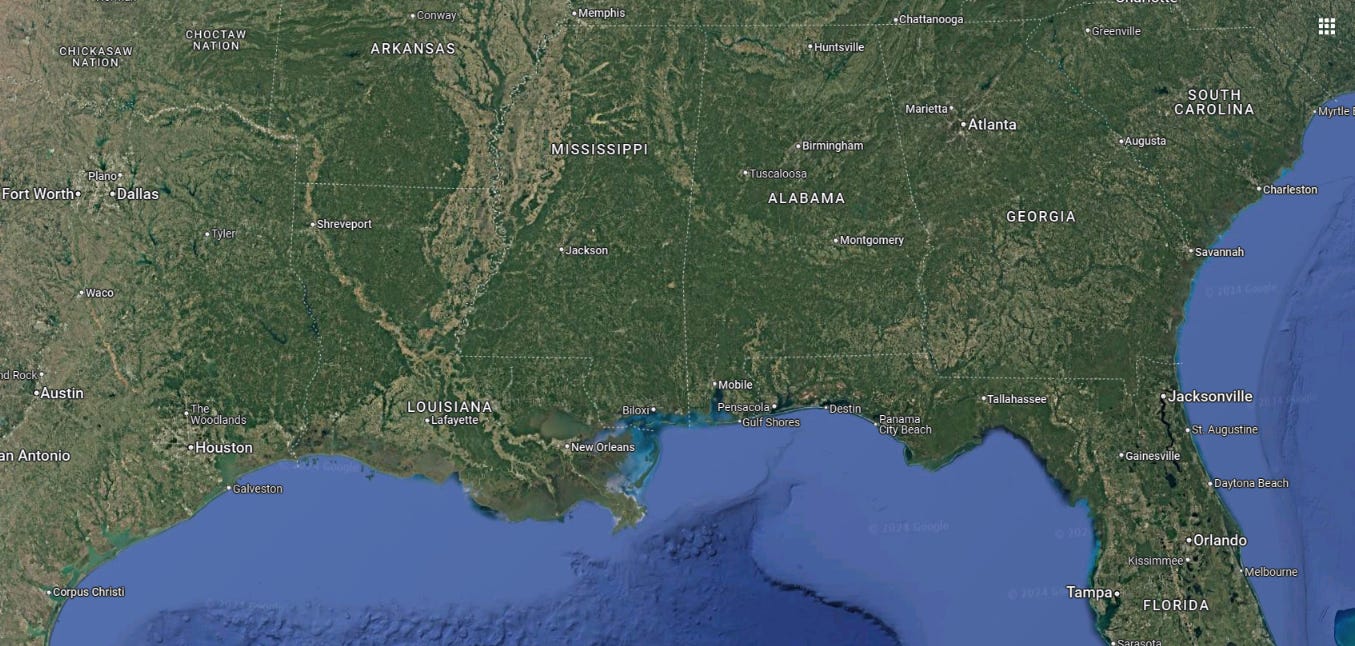

“Refuge of the Roads”: Somewhere along the Gulf of Mexico

The final track on Hejira is something of a thesis statement. What the road, the highway, represents on this album is a kind of refuge, from the difficulties of life, from responsibility, from everything that can tie you down. And this song most faithfully represents Mitchell’s peripatetic journey, going from place to place and meeting different people, and never staying for long. What she’s looking for is always in the next town, the next state, the next horizon.

The only references to location in this song come in the verse where Mitchell describes a spell she has “with some drifters / cast upon a beach town”. She specifically mentions the Gulf of Mexico, and also the supermarket chain Winn Dixie, which operates in the Deep South. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly where she is, but it’s likely somewhere in coastal Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, or Louisiana. We do know that she stopped off in New Orleans, so it could be around there.

The song begins with a meeting with the Tibetan Buddhist Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, and ends in the same spirit, with a photo of the Earth seen in a highway service station. By now it’s “the month of June”, summer; time has passed. Mitchell reflects that you can’t see any cities, or roads, or people in that photo of the Earth, least of all herself and her “baggage overload”, which has a double meaning here. But after this moment of existential pondering she moves on, “westbound and rolling, taking refuge in the roads”, on her way home.

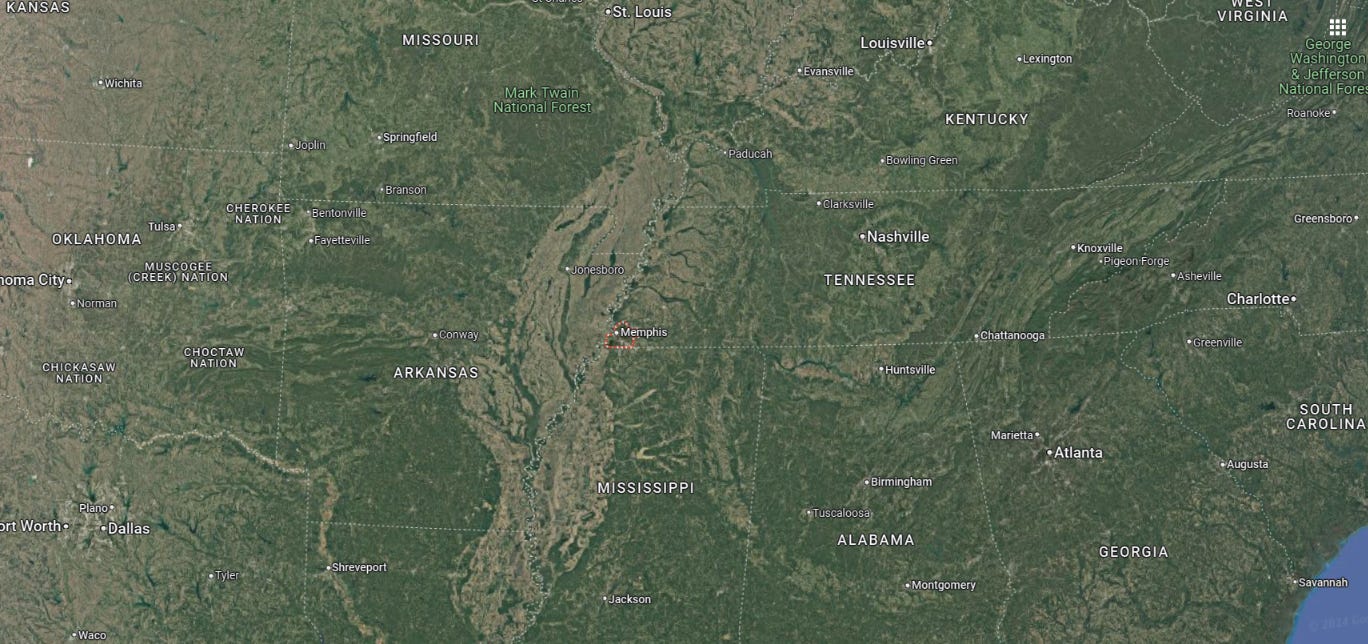

“Furry Sings the Blues”: Memphis, Tennessee

“Old Beale Street is coming down”, goes the opening line of “Furry Sings the Blues”, Hejira’s third track. The famous Beale Street in Downtown Memphis was once a thriving haven of debauchery, gambling and blues clubs. Its heyday was in the 1920s, but by the 70s when this song was written, it has fallen into disrepair. The shops have closed, the street is run-down, and there’s a palpable sense of wistful nostalgia and lost glory about the place. (It has since been revived as a tourist attraction.)

The two central characters in this song, aside from Joni herself, are the ‘Father of the Blues’ W. C. Handy and the blues musician Walter “Furry” Lewis. Memphis is known as one of the birthplaces of the blues, and in the first verse we see a bronze statue of Handy, holding his trumpet. Mitchell then pays a visit to Furry and watches him giving a performance.

It’s unclear when or why exactly Mitchell might have taken this detour inland, given that she was travelling along the southern coast and is headed for the west coast. It would seem quite far out of the way. But it looks like she might have come up from the south coast to get to the I-40, which passes through Memphis and stretches all the way to California. Alternatively she could have taken the I-10, which goes along the southern coast directly to Los Angeles.

Another mystery is the mention of a limo in the final verse, which would seem to contradict the fact that Mitchell was driving across the country in a borrowed car, and without a licence at that. The glamour would seem to be out of step with what she’s been doing so far. And not only is it a limo, but it’s “our limo”. Could it have been a prior visit, on a different trip, which she is now recalling? Was she not alone? It’s hard to say. But it’s still in the spirit of the journey we’re on, and part of the story of Hejira, so it doesn’t really matter.

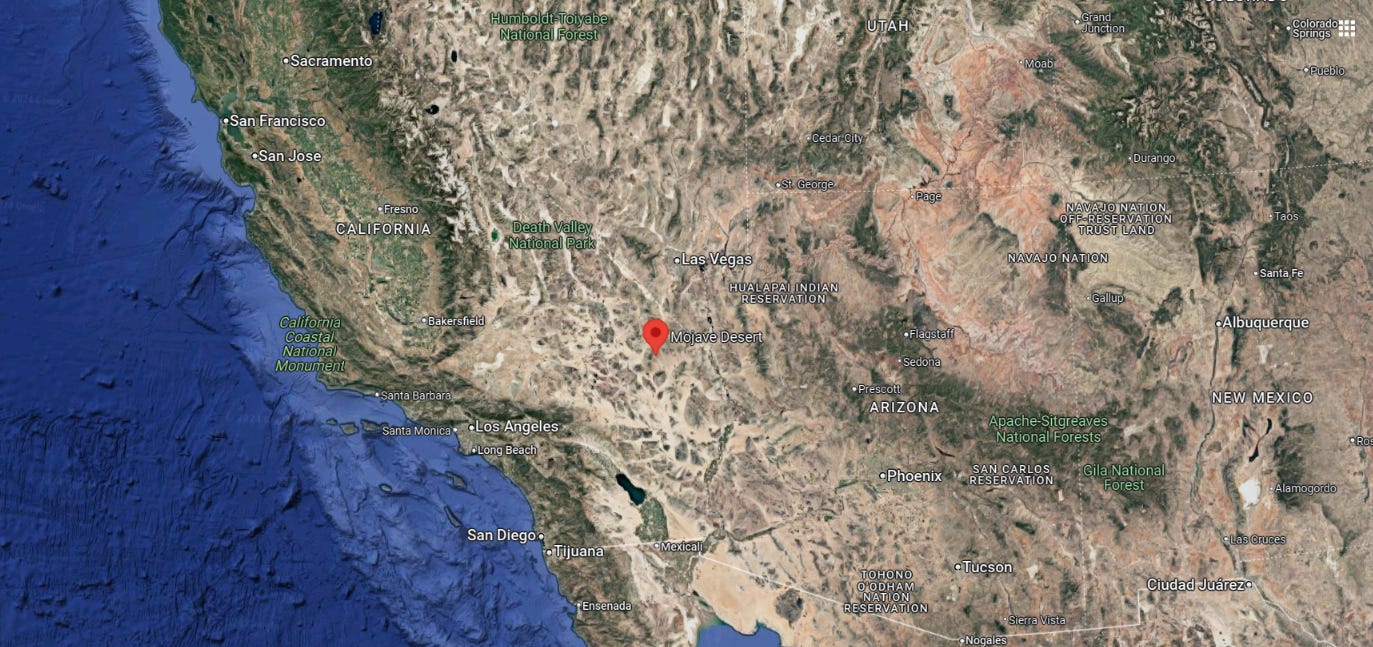

“Amelia”: Mojave Desert / Sonoran Desert

The final leg of our journey sees Mitchell “driving across the burning desert” en route to Los Angeles. “Amelia” is, among other things, an ode to the aviator Amelia Earhart, and Mitchell identifies with her as a fellow woman on a solo journey, conversing with her throughout the song about a relationship which has come to a sad end: “Amelia, it was just a false alarm”, she says. The song is also about, as she puts it, “the cost of being a woman and having something you must do”.

Depending on whether she took the northern or southern route home, Mitchell could be either in the Mojave or the Sonoran Desert here. They’re directly adjacent to each other, so you can take your pick. I’m inclined to go for the former, as it fits better with the narrative I’ve created which stops in Memphis.

In the final verse, Mitchell stops at “the Cactus Tree Motel”, which is a reference to an early song of hers called “Cactus Tree”, about a woman who is compelled to make her own way in life. And it seems that at this point, that same woman is still “so busy being free”.

So there you have it. Now you can take your very own Hejira road trip, if you feel so inclined. According to Google Maps, it would take you 105 hours to drive the whole thing.

The road calls to us all in different ways. We all have things we want to run away from, or to. And with people like Joni Mitchell for company, we can hopefully find some satisfaction in the journey itself.

Sources:

Joni Mitchell: Hejira — Jenn Pelly, Pitchfork

Hejira — Laura Snapes, Uncut

Great piece! Now, here's my chance to get nerdy about one of my favourite songs: Joni visited Furry Lewis on February 5th 1976 during her headline tour (hence the limo), the day after playing a concert at Mid-South Coliseum in Memphis (Feb 4). She talks about the visit in the intro to the song on Disc 2 of Archives Vol. 4, and at the end of the interview archived here: https://jonimitchell.com/library/view.cfm?id=460

She had already added 'Furry Sings the Blues' to her setlist by the Cincinnati show on Feb 10th, as several reviews mention it.