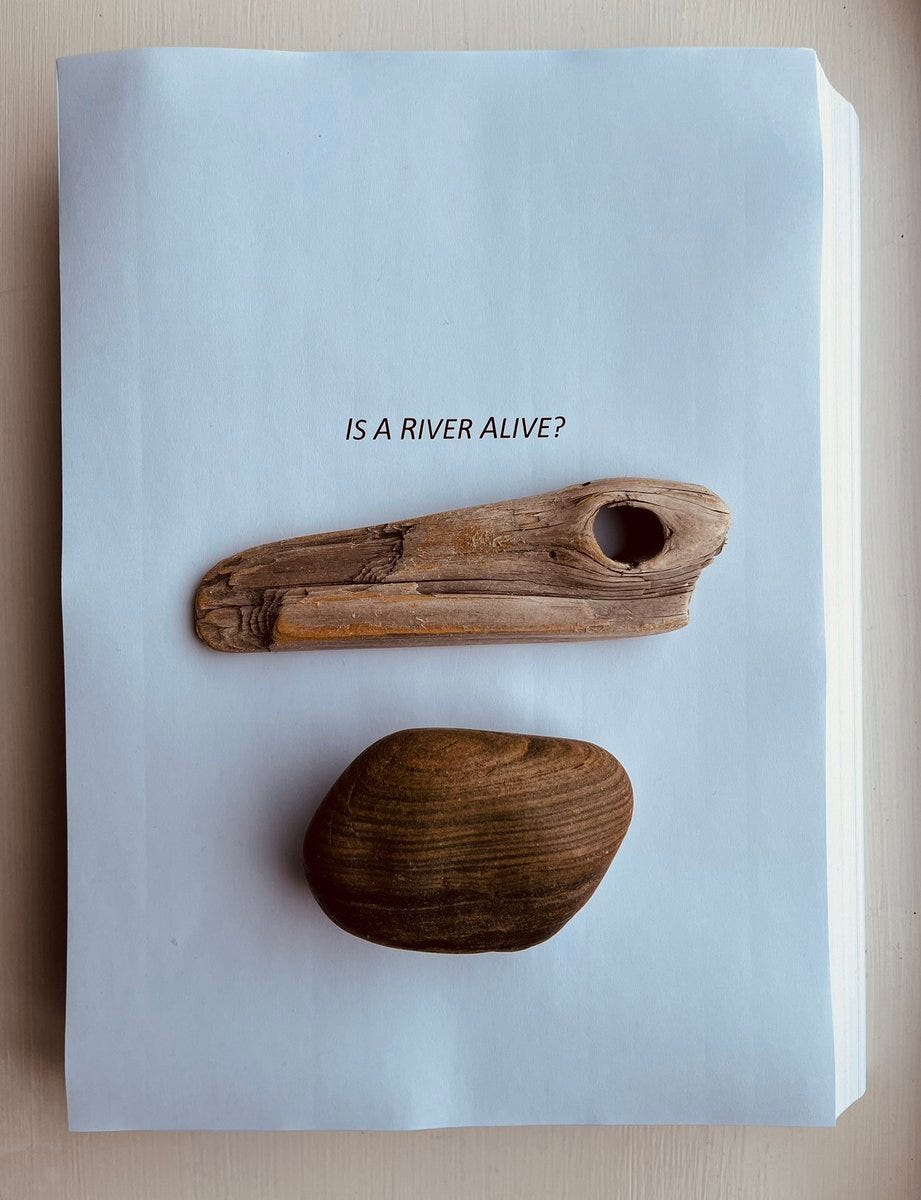

Is a River Alive? could have been a very short book. On a regular walk to school near his home in Cambridge, Robert Macfarlane is telling his son about the new book he is working on. He tells him the title, and in response, his son replies immediately that “the answer is yes!”

But it is not such a simple question as that. The long answer depends on a number of factors – the most important of which is, what exactly do we mean when we say ‘alive’? Who or what gets to be deemed as alive? To what extent do we extend our capacity to view the world as animate, as living?

The question of whether or not rivers are alive is particularly pertinent to this moment in history. In the United Kingdom, just for a start, only 14% of England’s rivers are considered to be in good ecological condition according to 2019 data. 100%, on the other hand, are polluted with chemicals. Water bills are going up and up, as are instances of Boil Water Notices after pathogens find their way into the domestic water supply. It would seem a puzzling turn of events that water, the primary precondition for life, has not only been exploited and monopolised by water companies seeking profit but has been degraded to such a point that it is no longer safe to bathe in the vast majority of waterways in this country. And as for the rest of the world, the picture is not much better.

So what went wrong? This is partly what this book seeks to find out. Over its three-hundred-odd pages, Macfarlane embarks on three journeys to three different rivers: one in Ecuador, one in south-east India, and one in northern Quebec, Canada. These rivers are sites of great natural beauty, but are also in peril – variously from mining, pollution, and damming. Through them, he finds out what it means for a river to be alive – and also what it means for a river to be dead.

Macfarlane studied English Literature at Cambridge, and published his first book, Mountains of the Mind, in 2003. The book explores the draw mountains have on our imaginations, what it is that compels us to go up into them, often in highly dangerous conditions and sometimes to our deaths. Mountains of the Mind became a classic of nature writing, and set the tone for the kind of writer Macfarlane was to be – a writer of deep engagement with landscape, a vast watershed of literary references, an academic’s trained critical eye, and a wandering curiosity.

Subsequent books The Wild Places and The Old Ways are both travelogues, detailing various paths taken, usually on foot, to wild and ancient parts of Britain and beyond. Underland takes an opposite approach, opting instead to delve beneath the Earth’s surface, and examine what these underground spaces have to say about geological time, or ‘deep time’. Excursions into music and film (and poetry with The Lost Words, now a staple of children’s libraries) have revealed an escalating moral imperative in his work, as has his increasing involvement with activist groups such as the MOTH (More-Than-Human Life) Program.

One of the main themes running through Macfarlane’s work is what he calls “landscape and the human heart”, and in Is a River Alive? he takes this to another level entirely. It is his most political book to date, and also his most personal. Tears are shed on several occasions. The moral framework is clear: drawing on a tradition of leftist thought and environmentalism, and borrowing from Robin Wall Kimmerer’s “grammar of animacy”, Macfarlane makes an impassioned argument to protect rivers from their impending ecological collapse using one of the most powerful tools we have at our disposal, the law. The Rights of Nature movement, with its emphasis on the world as living entity and the growing legal standing of this belief, is key to understanding the argument. Rivers are not just things that flow logically from source to sea; they are beings who flow, who tumble and rush and churn in a perpetual becoming. They are life in motion. One of the most effective ways we have to protect capital-N Nature is to endow it with the same rights and the same subjectivity we reserve for people. You might say that rivers are people too.

Is a River Alive? pushes at the limits of non-fiction. It incorporates poetry, song, and myth, normally considered to be outside the remit of what non-fiction is allowed to do. The effect is one of collage, a blending of different genres together to form a polyphonic form of storytelling.

The book starts off strongly, introducing the motif of The Springs, which comes back as interludes between the three main sections, offering welcome respite from their intensity; and the introductory chapter, “Anima”, demonstrates Macfarlane’s gift for synthesising a wide range of source material to great effect. The three main journeys are narrated in immersive detail, but detours into such delightful subjects as LiDAR imaging are sprinkled throughout to break up the action a little.

It is on his final quest, to the northern wilderness of Quebec, that the different streams of narrative come together. The river in question is the Mutekehau Shipu (meaning “river who flows through rocky cliffs”), in the traditional Innu homeland of Nitassinan (“our land”), which comprises the eastern part of the Labrador Peninsula. He is to travel a hundred miles by kayak, from Lac Magpie to the river’s mouth. And like any sensible person, he does not go alone but with a group who knows how to survive in the wilderness.

He is given strict orders by Rita Mestokosho, a local resident and poet, to leave behind his notebook, fast for 24 hours, always pitch his tent facing east where the sun rises, and to make an offering to the river every morning. All of this in the service of tuning into the land, “to wake up not the consciousness but the heart”. He humbly submits to her Indigenous wisdom. And in so doing, he begins to shed his identity as writer, as human observing landscape, as a being in a hierarchically constructed natural order.

The going is tough. The days of toil, rowing into high winds and down dangerous rapids, exert a slow obliteration of the self. The river is astonishing in its power, not just indifferent to the humans who attempt to traverse it but at times openly hostile. Eventually, through brute force, he begins to strip away the layers separating himself from the river – he becomes the river, the river becomes he. He is “rivered”.

This section contains some of the book’s most novelistic flourishes, and Macfarlane takes a number of stylistic risks – including several paragraph-long sentences which wouldn’t feel out of place in Samantha Harvey’s Orbital, for instance. It is fitting conceptually when “full-stops leave the building”, as language itself becomes water-like, fluid and sinuous, rushing along as the rapids sweep him up and toss him about. It’s a commendable effort, but Macfarlane is not a novelist, and these passages often don’t quite work. They end up collapsing under their own weight, the specificity of language failing to heighten the drama enough to justify itself. His shorter, sharper sentences are much better, and make more of an impact.

His main task on this journey, above all, is to ask the river a question, and he only has one shot at it, so he takes his time in finding it. When he does, he is looking into a gorge from the shore near the end of the river’s course, the rapids thundering below, and, as does Suzanne in Leonard Cohen’s song, he “lets the river answer”. The river speaks, sending up the answer not just to his question of it but the question of the book itself. It is the river’s Yes.

As for what that answer is, you’ll just have to read it and find out.

More than any other of Macfarlane’s books, Is a River Alive is a call to action. It is a call to reassess the way we think about rivers, and thus the way we think about the natural world at large. In fact, it invites us to dissolve our distinctions between the natural world and the human world altogether, offering instead a union between the two, a merging into a larger, more expansive vision of what ‘life’ is. While it may not have the warmth of his earlier work, one could argue that warmth is not what is needed right now in the age of extinction that we’re living through. This is clearly a book designed to persuade and convert, righteous in its views and clear in its convictions, and it certainly pulls you into its current. Time will tell if it does for rivers what Richard Powers’ The Overstory did for trees.

The book is many other things as well – an affirmation of hope, that “despair is a luxury”; an elegy; a test of faith; a spiritual journey. But it is also a warning: water is life, and we ignore this fact at our peril.

Jack!! I have been waiting forever for this book! Thank you for choosing to write this essay. I plan to spend more time with your words this weekend. For now, on a skim—my thanks, a like, and a restack. 🌱📘💚