Recently, I watched a documentary from 2019 about the writer Margaret Atwood, called A Word After a Word After a Word is Power. The documentary follows Atwood as she travels the globe for various engagements, sometimes alone, sometimes with friends, sometimes with Graeme Gibson, her late partner, who died shortly after the film was made. We cut between her present-day adventures and biographical segments charting her beginnings and rise to literary stardom, including interviews with family members and contemporaries. It’s a great documentary which captures brilliantly what makes Atwood such a distinguished figure in the literary and political landscape.

The title, one of her most popular quotes, is taken from a poem of hers called “Spelling”. The poem starts with a description of her daughter learning to spell using plastic letters, and goes on to ruminate on the nature of language, womanhood, and power.

The phrase a word after a word after a word is power can have many different meanings. Power can mean many different things. I reference Atwood again, in an interview she gave on Charlie Rose (yes, I know) in 1994:

As writers, we understand the power that words have perhaps more than anyone else, and not just the power for good. The positive side: Words can help you name things that you need to know about. They can help you communicate with people that you love. They are a vehicle for communicating ideas that can change people for the better. Writers know this well; it’s their whole thing.

However, words can also be used to communicate harmful ideas that pit people against each other and drive them apart. Words can stoke hatred and incite violence. Again, writers know this well from our observations of people — as does anyone who has followed politics in recent years.

And it’s not just a recent thing. Almost a century before Trump told his supporters to storm the Capitol and undermine American democracy, Hitler used the then relatively new format of radio to broadcast his hateful views and advocate for the extermination of Jews, among other groups. Many people listening at that point probably thought what a load of old twaddle he was talking, and such things were preposterous to even think about. Then the Holocaust happened. Moral of the story: Pay attention to what people say they want to do if they get the chance, because they might just do it. This is what words can do.

In “Spelling”, Atwood juxtaposes the innocent image of her daughter learning to spell with images of horrific violence against women:

“I return to the story

of the woman caught in the war

& in labour, her thighs tied

together by the enemy

so she could not give birth.”

Such stories are not hard to find. Violence against women is such a common theme in Atwood’s work because it is such a common theme in human history.

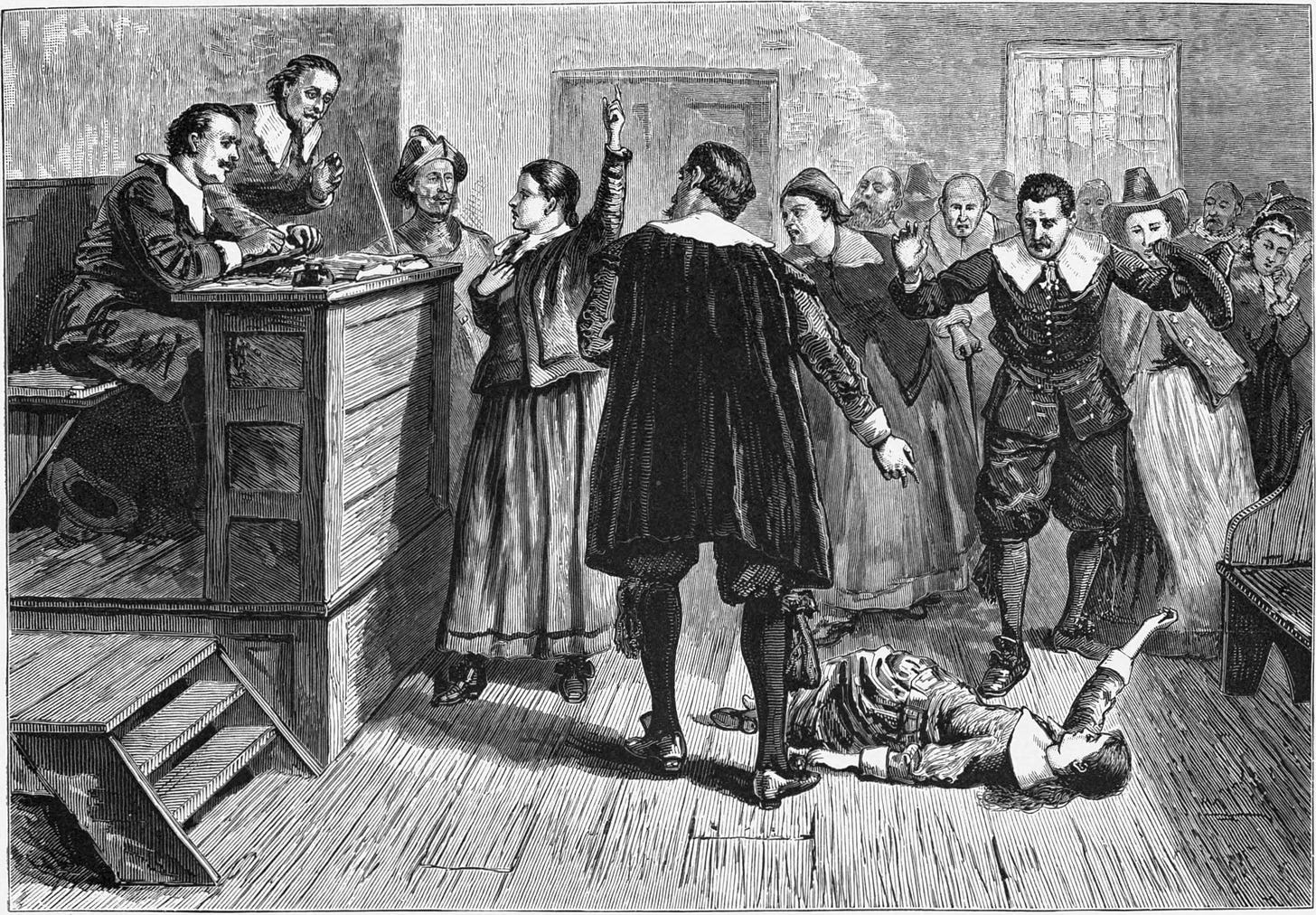

Then comes an image of violence related specifically to speech:

“Ancestress: the burning witch,

her mouth covered by leather

to strangle words.”

“Ancestress” is probably referring to Mary Webster, a possible predecessor of Atwood’s, who was tried for witchcraft, acquitted, but was then hoisted up onto a pole by the townsfolk anyway and left there overnight to die. Atwood would give Webster a poem of her own later on in her career, called “Half-Hanged Mary”. Spoiler: She doesn’t die.

The image of covering someone’s mouth so their words can’t be heard while they are being burned to death is a horrific one, not just because of the cruelty of the act but because she cannot use her words even to deliver a final message. Words are freedom in cases like this. But she does not speak. Her selfhood is taken away; she is reduced to a thing to be burned, erased, turned to ash.

Related to power and language is ‘freedom of expression’, which has been coming up a lot recently. As people’s views clash over various political topics, the words ‘freedom of expression’ or ‘free speech’ have been frequently invoked. But let’s be clear: Freedom of expression and free speech are two different things. Some people appear to be conflating the two, and using it to justify inflammatory speech and to say that they should be able to say whatever the hell they want without consequence. But freedom of expression doesn’t mean saying whatever you want, as ‘free speech’ suggests; it means being able to be disagreeable without being thrown in jail (or otherwise shot) for it. Having a disagreeable opinion is one thing, inciting violence against certain groups or saying that they should not exist is quite another. This particularly comes up a lot in the debate over trans issues, which I might explore in an essay of its own, if I’m feeling brave enough. (Suffice it to say, I am in support of trans people existing generally, no matter what their age is or what other mental health issues or neurodivergences they may have.)

One of the controversies of the moment here in the UK has to do with the Royal Society of Literature, where changes in leadership and in how it admits fellows have prompted backlash from senior members, who feel they are being sidelined by “radical” new policies introduced by president Bernardine Evaristo, director Molly Rosenberg, and chair of council Daljit Nagra.

I find Evaristo’s response to the claims to be quite convincing, apart from her defence of the organisation’s failure to make a statement in support of Salman Rushdie, who was nearly fatally wounded in a knife attack in August 2022 — apparently because he is problematic in some way. She writes that the Society “must remain impartial” in matters to do with writer’s issues, such as an attempt on a writer’s life because of what he has written. But if the Society “is doing such important work supporting and celebrating writers”, as Evaristo claims, then shouldn’t that include condemning attempts at murdering them? Words, as we know, are powerful. So is a lack of words.

I want to conclude with another quotation from Atwood’s poem which I think is just brilliant:

“At the point where language falls away

from the hot bones, at the point

where the rock breaks open and darkness

flows out of it like blood, at

the melting point of granite

when the bones know

they are hollow & the word

splits & doubles & speaks

the truth & the body

itself becomes a mouth.”

When the body itself is a mouth, and when the word speaks the truth, it can be easy to think that everything you are saying is gospel. But you can get lost in words, too. They can obfuscate, distort your view. It’s important to scrutinise not only what other people say, not only what you say, but language itself, in all its capabilities for good and evil. A word after a word after a word is power. And great power comes with great responsibility.

Jack, my favorite of yours, this far.

Just so wise.🌱